Written by Jayant Dalvi, Savitri explores different perspectives of marriage and its relevance in today’s world.

Theatre lovers in Delhi have been watching with keen interest the plays by eminent Marathi playwright Jayant Dalvi from time to time. One of his plays Sandhya Chhaya, which was presented by the Repertory Company of National School of Drama under the direction of Uttara Baokar in 1978, got a tremendous response from the audience. Its popularity enhanced with the superb acting by Manohar Singh and Surekha Sikri in lead roles. In recent years, Nadira Zaheer Babar’s Ekjute Mumbai’s production of this play had several shows in different parts of the country that deeply stirred the emotional world of the audience. This past week we watched Dalvi’s another play Savitri which was presented by the Fourth Dimension at Akshara Theatre, which seeks to explore the truth about conjugal life and the relevance of the institution of marriage in the context of changing socio-economic conditions.

Betrayal of feelings

Directed by Praveen Kumar and translated into Hindi by the playwright himself, the protagonist of the play is Aparna, a young woman who passes through emotional turmoil. When she was in her teens she fell in love with a handsome youth next door. Soon enough they were separated. But the sweet memory of that adolescent love always remained with her. In contrast, she has the bitter memory of the stigma on the family because her mother eloped with her tabla teacher. She grows up under the dark shadow of ill-reputation of the family.

However, a young man working as a lecturer, who resembles with her first lover, marries her. Their happy days as the newly-wed couple do not last long. Though the couple is facing financial hardship, the husband wants her to resign from her job. The wife resists. Enters another man, who happens to be the managing director of the company in which Aparna is working. The managing director is smart, gentle, and sweet in conversation. Aparna gets promotion and soon Aparna and the director come closer after her separation from her husband and little son. However, the living relationship between Aparna and the director ruptures. The director returns to his family, leaving Aparna alone. The director is dismissed from service as a result of leading a scandalous life and his miserable failure to handle labor unrest. Aparna resigns. Now known as a woman of disrepute, she gets job offers which are an affront to the dignity of a woman.

The play opens with Aparna arranging household belongings in a newly rented house, waiting for her husband. The room is frequently visited by women living in neighboring houses. There is a woman who reveals that her daughter has eloped with her lover, painting a rosy picture of the husband of her daughter, boasting about his high economic standing. There is another woman who talks of women empowerment and women’s liberation. She has not much respect for marriage and stands by Aparna. There is another woman who is spineless and for her the ultimate source of wisdom is her husband. Frequently Aparna’s close relative also visit revealing the bitter relationships between husband and wife and yet they live in the same house. To add ironic touch to this theatrical canvas of dysfunctional families, the women perform Bat Pooja with ritualistic fervor, seeking everlasting happy domestic life.

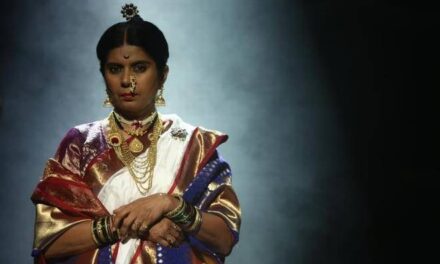

A scene from Savitri | Photo Credit: Special arrangement

The playwright has skillfully weaved brief narratives about different women in the life of Aparna, projecting a larger image of the suffering of women in a world dominated by men who have the last laugh, leaving women as helpless creatures. To reflect the antithetical emotional impulses inside Aparna, there are two objects on the stage—a huge mirror and a window that opens on the crematorium ground. She involuntarily looks in the mirror, admiring her beauty and when she is sad she looks out of the window, watches the crematorium ground.

To comment ironically, the playwright has given the title of Savitri to his play instead of giving it the title of Aparna to provide a contrast between mythological Savitri and modern Savitri—Aparna.

The production seems to be inadequately rehearsed. The director should have worked on the voice of the actors to convey the emotional ebb and flow of the characters. Akshara Theatre is a kind of intimate theatre. The dialogues delivered by some of the performers in such a low voice that these are not even audible to the audience sitting in front rows. The director claims to follow a realistic style of presentation. Some of his actors follow the emotionally restraint acting style. What is required is that the tone should be lifted and the pace be quickened to create an emotionally tense atmosphere on the stage to involve the audience.

In the lead role of Aparna, Stuti Rai could have created a moving portrait if she had paid attention to her dialogue delivery which remained partially audible. Nitin Tomar as the Professor husband of Aparna acts in a highly restraint style and could not reveal the inner conflict of his character with emotional and dramatic force. Pinky Negi as Mausi, a bold and assertive young woman, acts admirably. Her Mausi stands by Aparna but towards the crisis in her life leaves her all alone. Minni’s Baijee is a religious woman who is leading an unhappy married life vehemently keeping her distance from her husband who has become alcoholic to escape from the humiliation inflicted on him by his suspicious wife.

This article originally appeared in The Hindu on May 25, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Diwan Singh Bajeli.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.