I attended a live performance of Acha Bacha, written by Bilal Baig and directed by Brendan Healy, at Theatre Passe Muraille, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, on Wednesday, February 7, 2018.

Bilal Baig is a young, queer, genderqueer, Muslim playwright and devised-theatre-maker based in Toronto. Baig’s parents were born in Pakistan, although Baig was raised in Mississauga, Ontario.

Acha Bacha, apart from minor amounts of miming and the flashback sequences, is a realist theatre performance; realism is maintained within the content of the flashbacks. Baig’s debut addresses the themes of identity conflict and acceptance: sexual identity, religious identity, cultural identity, and acceptance of each, both separately and together.

Tied into the main themes, the play touches upon a few other issues, such as bullying, norms, pedophilia, relationships, love, understanding, misunderstanding, acceptance, rejection, and ignorance. Acha Bacha is quite relevant, as the story addresses current social issues affecting people who identify as queer from South Asia and the Middle East, specifically people of the Islamic religion and culture in the Pakistani diaspora.

Acha Bacha tells the story of a young queer Muslim man named Zaya (Qasim Khan) and the struggles he faces because of a lack of acceptance and understanding from his partner, his mother, and himself. The play opens with Zaya and his genderqueer partner, Salim (Matt Nethersole), partaking in an intimate act, although Zaya’s thoughts seem to run elsewhere. Instead of being fully involved in the moment with Salim, Zaya finds himself thinking of an older man in a shalwar kameez by the name Maulana (Omar Alex Khan), who is portrayed onstage as a flashback that only Zaya can see. Maulana was the owner and imam of Zaya’s childhood mosque, although Zaya seems unsure of why he is seeing Maulana and pushes him from his mind. The flashbacks continue throughout the scene, and Salim notices that Zaya seems uncomfortable. Thinking that it has to do with their current intimate relations, Salim asks Zaya if he wants to stop. Zaya, continuing to push away the flashbacks, reassures his partner that he wishes to continue, and the scene essentially ends there.

Later, when visiting his Ma (Ellora Patnaik) in the hospital, Zaya reunites with an old friend, Mubeen (Shelly Antony). Mubeen is the son of Maulana, and this encounter causes Zaya to experience more flashbacks involving his old imam and Islamiyat teacher. Years before, the day after an Eid party, Maulana closed his Mississauga basement mosque without notice and moved away to Kitchener with his son Mubeen. Zaya believes that he, himself, had something to do with the sudden closure of the mosque, and he is determined to uncover the secrets lost in his mind. Although Acha Bacha takes place in the present, there are several flashbacks throughout the play composed of related events from Zaya’s past as he tries to uncover what happened between Maulana and himself years ago prior to the Eid party on the same night.

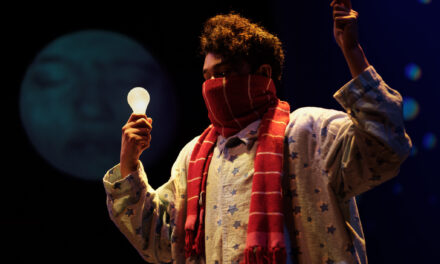

Photo of Bilal Baig by Tanja-Tiziana. Design by Lucinda Wallace, courtesy of Buddies in Bad Times Theatre

Despite the small cast of only five bodies on an almost empty stage, the actors were talented and conveyed the story as convincing and believable. The set (Joanna Yu) and lighting (C. J. Astronomo), however minimalistic, were effective, as they helped keep the play contained and focused on the characters in the story and the dialogue. This artistic choice allowed the audience to become further immersed in the realism of the performance. The technique highlighted the story aspects of the play by portraying the events in Zaya’s life as realistic experiences.

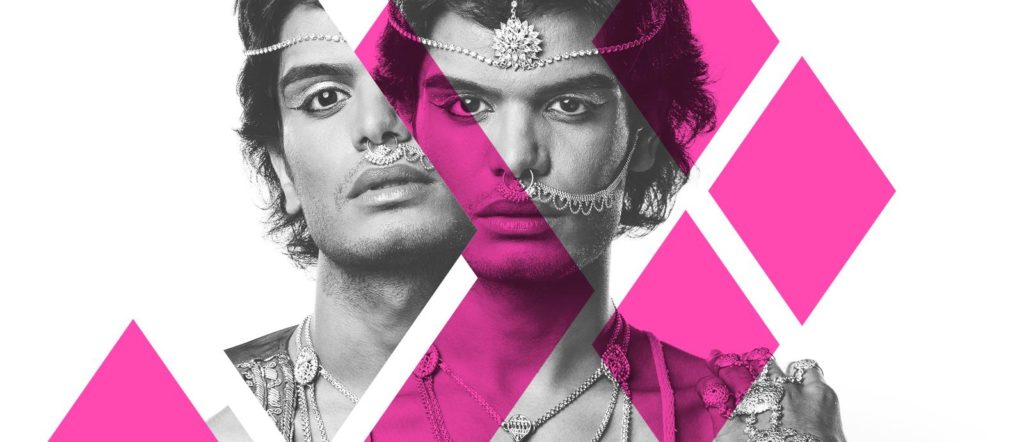

The character’s costumes (Joanna Yu) also complemented the realist aesthetic of the performance, as they were normal, everyday clothes, yet also tied into the story, as they represented the main themes of identity, culture, sexuality, and religion. Zaya wore ripped skinny jeans, trendy shoes, and a V-neck T-shirt representative of men’s fashion in 2018 Canada and thus of Zaya’s Canadian cultural identity.

Salim wore a mixture of traditionally masculine and feminine apparel, showcasing their genderqueer sexual identity as well as their Canadian and Muslim cultural and religious identities: facial hair, lipstick, hijab, men’s underwear, woman’s brassiere, painted nails, trendy shirt, pants, and shoes. Salim’s outfit upset Zaya’s mother; it made her feel uncomfortable, and she did not accept it. Ma wore a hospital gown, and a sari with a hijab, showcasing her Muslim cultural and religious identities.

Mubeen wore khaki pants and a buttoned flannel shirt; Ma compared Zaya to him and wished her son was more like Mubeen, and Mubeen’s clothing can be interpreted as physically representing that wish. Mubeen’s clothing reflected cultural identity if any at all. Maulana wore a shalwar kameez and a taqiyah, representative of his Muslim cultural and religious identities as well as his position as imam of the mosque. The costumes also subtly differentiated between time periods: Zaya’s shirt and jeans were different when he was younger from his present-day attire as an adult.

Most of the dialogue was in English, although both Salim and Ma spoke Urdu. Salim mixed Urdu in with English, and Ma spoke almost entirely in Urdu. Mubeen also spoke Urdu, although only to Ma and never to Zaya. In contrast, Maulana spoke almost entirely in English and rarely in Urdu, if at all. Zaya, apart from a prayer that Maulana got him to recite, spoke only in English. This was significant to the performance in two ways.

First, it seemed that Zaya’s refusal to speak Urdu might be related to his identity conflicts; culturally, Zaya is comfortable speaking English because he is Canadian, and queer sexual identity is widely accepted in Canada. Second, it makes sense for the play, as intended for English audiences, to have the protagonist speak in the tongue best understood by those audiences. As a resultant, Acha Bacha made what was said in Urdu very clear through gestures and inferences from what other characters, mostly Zaya, were saying in English.

Having a little, albeit limited, knowledge of Hindi myself, I was able to understand some of what was said in Urdu, as the two languages share many common words. As a result, I feel that my experience of the play was slightly different from that of those who speak only English and were left to understand through inference and gesture alone. Personally, as I related to the mixture of the two languages, my experience was slightly homely and comforting, as if I were included, as opposed to that of those who did not and who thus may have experienced uncanniness and been slightly uncomfortable, as if they were an outsider. I am sure that both outcomes were Baig’s intention, as they are tied directly to the themes of acceptance/rejection, ignorance, and understanding/misunderstanding.

The phrase acha bacha in Hindi and Urdu literally means good child, although in the context of the play it can be concurrently understood as good boy. Zaya is expected to be a “good boy,” meaning that he must behave as if his sexuality is a misbehavior and wrong. This is a focal point of the performance and an intended message pertaining to the issue that so many queer Muslims must face in their own lives.

When Zaya expresses his sexuality, he feels good about himself; although in another way he also feels bad for his mother. In contrast, when Zaya suppresses his sexuality, he feels bad about himself, although in another way he also feels good for his mother. This aspect of the play makes the title Good Boy so symbolic, ironic, and poetic. If Zaya is being and feeling “good” in one way, he is also being and feeling “bad” in another. The overall conflict that the play presents is that it is up to Zaya to be either a “good boy” to his mother and tradition or a “good boy” to himself.

Culturally, Zaya identifies as Pakistani-Canadian and Muslim. Zaya also identifies as Muslim religiously. As it is possible to identify as Muslim both culturally and religiously, there is the option to identify as one and not the other. The Islamic faith is deeply rooted in the cultural and social norms throughout the Middle East, similar to Christianity in Western society; for example, one does not necessarily have to be religious to celebrate Christmas or Eid.

In Acha Bacha, Zaya’s conflicts arise from the character’s queer sexual identity, as he seems to feel that it interferes with his cultural and religious Muslim identities. Despite the scientific evidence that queerness is biologically natural in all mammals, many interpreters of different religious faiths still believe that it is wrong.

In contrast, one can be content identifying both as queer and as Muslim. Salim is representative of this and is arguably more faithful to Islam than Zaya is. Salim is not dealing with identity conflict on the same level, if even at all, because they are content with all identities coexisting. This demonstrates how one can find balance with their identities and live happily and healthy. The issue here is Zaya’s mother’s lack of acceptance of Salim, as well as Zaya’s own conflicts that cause discrepancies within their relationship. It is proof that one can identify both as of the Muslim faith and as queer without any internal conflicts, which is another message the performance is trying to convey.

Ma, of traditional Muslim faith, believes Zaya’s sexuality to be a punishment for insufficient prayer. She treats his sexuality like an illness and a burden that she and he both must bear. In a flashback scene to when Zaya is little, Zaya asks his mum to paint his nails, and she scolds him and tells him with disappointment that he was “so good.” This is an explicit example in the performance of just how hard and scary it can be when your own family does not accept you for who you are. Ma is unaccepting of Zaya’s wishes, although she paints his nails anyway because she loves him. But she tells him to take the paint off before they go out and to hide it from the owner of the mosque.

Zaya deals with childhood trauma arising from his encounter with Maulana, although he is unsure of what truly happened. Over the course of the performance, Zaya tries to piece together the truth through his flashbacks. He knows something happened between him and Maulana the night of the Eid party. He knows that it is why Maulana closed the mosque and moved away with Mubeen, although he does not know what it was. It seemed that Zaya felt this encounter was the source of his conflicts and the root of his flashbacks; therefore, the only solution was to try to find out the truth.

Salim and Zaya. Photo by Michael Cooper

Acha Bacha ends ambiguously and abruptly. Salim tells Zaya in Urdu that they love him, and Zaya replies back the same but in English. It is up for debate whether this scene really occurs or whether it takes place only in Zaya’s head. Regardless, the significance of this scene is that maybe sometimes love just is not enough. By this point, it seems that Zaya has uncovered the secrets of his past, or at least he is satisfied with what he thinks occurred with Maulana. The surrounding issues are still at play, as the conflict is still present in Zaya’s life. The ending is meant to be this way to convey the message that the issue of identity conflict in real life is not always resolved. Acha Bacha has the potential to push for social change that abolishes more of the ignorance of and misunderstanding towards an individual identifying as Muslim and queer.

Recently there has been an increase in theatre performances telling the stories of Middle Eastern and South Asian people in Toronto. Theatre is a great tool for connecting the world, as it has the power to teach audiences about other cultures through the stories told.

Overall, Baig’s debut Acha Bacha had a great cast and told a story that has not yet been staged at a major Toronto theatre. We can only look forward to what this young playwright has in store for the future.

Works Cited

Knegt, Peter. Meet The Emerging Creators From Canada’s Longest-Running Festival Of New Work. CBC, February 16, 2017. http://www.cbc.ca/arts/meet-the-emerging-creators-from-canada-s-longest-running-festival-of-new-work-1.3984222 (accessed February 16, 2018).

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Christopher Taylor.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.