The language we speak is, in a deep sense, who were are. But what about learning a second language, and how does this affect our sense of our own identity — and how we relate to other people? Such fascinating questions are at the heart of Iranian-American playwright Sanaz Toossi’s 2023 Pulitzer Prize-winning play, English, which premiered off-Broadway in 2022, and now arrives for its European premiere at the Kiln theatre, simultaneously rounding off Indhu Rubasingham’s final season as artistic director (her next job is head of the National Theatre). The production is coproduced by the Royal Shakespeare Company as part of Daniel Evans and Tamara Harvey’s first season as co-artistic directors.

Set in a classroom in Karaj, Iran, in 2008, the story is about the efforts of four adult Iranians — three women and one man, ranging in age from teenager to fiftysomething — to learn the English language for TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language). Their instructor Marjan, who spent several years living in Manchester, in the north of England, alternates between enthusiasm and a wry despair while they go through their various exercises, as she admonishes them constantly to “speak English” rather than Farsi. Slowly, over 90 minutes, a picture is built up of their individual characters and their motives for learning the language.

Marjan’s students are a varied bunch: Elham is a bright medical student who needs a English-language certificate because she wants to go to medical school in Australia; Roya is a grandmother who really wants to connect with her grandchild, who lives with her son in Canada and who only wants to speak English; Goli is the energetic, and often comic, teenager; and Omid is the situation’s mystery man — he speaks the language exceedingly well so why is he in the class at all? His vocabulary is excellent, and at times he even knows as much about English as Marjan.

Toossi’s mild-mannered comedy is essentially a rather slow-moving meditation on how language is central, intimate even, to our sense of self. So learning a foreign language — ironically here for the British audience this “foreign language” is English — means that you can acquire a second self, or an expanded first self, which opens up various possibilities that are closed to people who only have one native tongue. The play also offers intriguing ideas about what it’s like when we hear ourselves speaking a different language, how this affects our subjectivity and our role in the world.

The play sees language as dynamic. Learning a new language is both a trial, with many frustrations and mistakes, and a kind of adventure, a journey of the mind. Toossi also shows that you can sometimes lose some of your ability to speak a second language, forgetting standard pronunciation and correct grammar. She sees the learning process as both a game and an imposition, with some added points about student competition and the personal politics of the classroom: how ethical, she asks, is it for a teacher to have a favourite, or to pick on one of the students?

The classroom setting gives the play a rather static feel, despite those episodes when the students throw a ball to each other while shouting English words for things that are, for example, green, and — because of its subject matter — it is inevitably rather wordy, and in this case rather worthy too. The students play language games, such as a “show and tell” speech about an eye pencil, do some inevitably funny role-playing and listen to recordings, including some brief snatches of American films. There is a gentle tone to all of this, despite Elham’s moments of anger, Roya’s moments of despair and Marjan’s moments of unrequited desire. By the end, I felt that the situation, while entertaining enough, lacks real dramatic punch.

In the playtext, Toossi’s dialogues involve two kinds of English, the first completely fluent, which is when the characters speak Farsi to each other, and the second more uncertain, more-accented to show that they are talking English, learning as they go along. A lot of the energy of the production has gone into making these alternate speeches both convincing and smooth. The Iranian-accented English sounds right to me, but I do wonder if it might have been better to have the actors speak Farsi, with subtitles, which would have been more pleasurable to the ear.

Some of the text includes comparisons between Farsi and English. At one point, Goli says, “English does not want to be poetry like Farsi”, before comparing English rather comically to rice: “English does not try to sink or get out of water.” Despite such vivid imagery I do think that the play could have given a more poetic impression of Farsi and said more about Iranian culture. Toossi plays safe by excluding any mention of religion or politics, and this feels like a gap. When the characters watch an American film as if it is a perfectly normal thing to do in Iran, is this really realistic?

There’s a neat contrast in the play’s comparison of speaking English as an enabler, a kind of Green Card out of the Middle East and into the West, and an oppressor: for some of the students English words feel wrong in their mouths, and they cannot express themselves truthfully. Elham, in particular, feels that her English self is a diminished one. As well as this, there is a quiet sense that the dominance of English as a global language is not only a passport to a better job, but also to better family connections in a diaspora, and of course it’s a marker of popular culture in film and music.

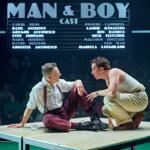

Directed by Diyan Zor, and designed by Anisha Fields, English is very well acted. Nadia Albina’s Marjan, who was renamed Mary during the nine years she lived in England, suggests much of the fun and some of sadness in learning, and forgetting, another language, while Serena Manteghi’s feisty Elham, Lanna Joffrey’s thoughtful Roya and Sara Hazemi’s energetic Goli are likewise excellent. Nojan Khazai makes his stage debut as Omid, whose secret shocks the others. With an ending that plays a linguistic trick all of its own, this is an interesting play of ideas rather than a compelling drama.

- English is at the Kiln Theatre until 6 July.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.