Nabaggala Lillian Maximilian has outdone herself by covering a lot of ground recently.

A few months ago, she premiered a dance theatre production, Nambi, and exhibited a short film, Faded in Berlin. And barely a month after the sojourn in Berlin, she was on stage at the Kampala International Theatre Festival.

It is safe to call Faded a work in progress as far as theatre is concerned; in fact, with the way Nabaggala works, many of her theatre productions are never in their final form, so she will always have something to throw in.

Faded was inspired by a series of interviews the performer did with women across different parts of Uganda. In the interviews, they talked about identity, skin colour, and why many people opt to have their shades or tones changed.

Call it shade-ism or colourism, the production tries to understand why women do it and what leads them to the decision – the findings are sad; media, pop culture, literature and a lot of material that people consume and make it look like having a fairer skin is guaranteed cultural beauty.

In Faded Nabaggala is seeking to reclaim her older beauty. (photo by Kaggwa Andrew)

This societal pressure to conform to a certain standard of beauty has detrimental effects on women’s self-esteem and perpetuates harmful stereotypes. Faded aims to shed light on these issues and challenge the notion that fair skin equates to beauty, promoting self-acceptance and embracing diversity instead.

The solo performance was the first dance production that the Kampala International Theatre Festival has staged since its inception. In an earlier interview, Deborah Asiimwe, one of the founders and directors of Tebere, said that they have always wanted to have dance theatricals but never got the opportunity before.

In the production of Faded, like the film, Nabaggala stars alongside her reflection and a voiceover she did herself. Unlike in the film, where the different stages of skin bleaching are explored, on stage we start with a lighter complexion. Nabaggala is seeking to reclaim her older beauty.

Of course, the production could be up for very many interpretations since it is as abstract as such shows come. But what the production, regardless of media, represents is a woman struggling with her identity, beliefs, and what the public considers beauty.

We follow her quest to self-discovery, later appreciating the reflection she sees in the mirrors.

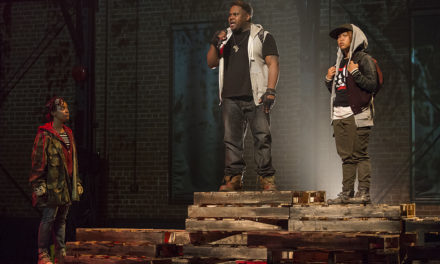

The way Nabaggala easily adapts her shows for spaces is a true sense of an artist in control of both the vision and story (photo by Kaggwa Andrew)

Throughout the performance, Nabaggala’s journey serves as a powerful metaphor for the societal pressures and expectations placed on women to conform to certain beauty standards. As she confronts her own insecurities and challenges the notion of what is considered beautiful, audiences are encouraged to reflect on their own perceptions of beauty and identity.

Ultimately, the production highlights the importance of self-acceptance and embracing one’s true self in a world that often tries to define us.

Besides all that, the productions shows how much Nabaggala has grown as a performer and writer; the way she easily adapts her shows for spaces, throwing in more props to cover for what she may not be able to get, is a true sense of an artist in control of both the vision and story.

This article appeared in The African Theatre Magazine on December 7, 2023, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, please click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kaggwa Andrew Mayiga.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.