John Ssegawa’s Golden Calabash, Ekimala Ebita Embuga opened at the National Theatre in Kampala running during the Christmas season from 23rd to 26th December 2023.

The theatre spent 2023 trying to find solutions to its predicament; questions have been asked, and in the same way, panel discussions have been held.

On his part, John Ssegawa believes theatre can only return to its former glory when it embraces the existing challenges but, in the same way, adapts and redefines the art.

His past two offerings, Zansanze, which was staged in 2019, and his latest, Golden Calabash, have been a testament to his willingness to learn, unlearn, and, at the same time, teach.

Golden Calabash, which made its world premiere at the National Theatre over the Christmas holiday, is not exactly a new production off the page; rather, it is a redefinition of a classic that Afri-Talent and Bakayimbira Dramactors previously presented as Ekimala Ebita Embuga.

See also: Kampala’s Tale of Two Theatre Festivals

Abby Mukiibi, Andrew Benon Kibuuka, and John Ssegawa then played the titular roles. However, when the play was restaged at the National Theatre, he says the aim was to interest a new group of actors in theatre; besides, the rest of the cast was relatively new and young.

From the time the curtains open at the theatre auditorium, a range of love stories that involve almost the entire cast are clear, but all unite in one passion: a secret desire to overthrow their leader.

The Golden Calabash is a coming-of-age political satire wrapped in a Kingdom of Bahehe, where a king will get a vote of no confidence the moment it is noticed that he’s no longer as strong as he should be. In that case, the son or daughter must replace him.

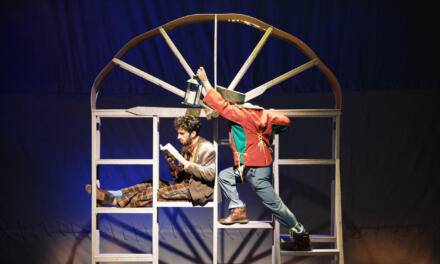

John Ssegawa’s Zansanze (2019) and Golden Calabash are a testament to his willingness to learn, unlearn, and teach at the same time (photo by Kaggwa Andrew)

The stage is lit a day after the wedding. There are rumours that the king failed to lift the calabash, but if that is not enough, the old or outgoing queen too refused to leave the palace for the new queen.

See also: Miangaly Theatre Company: Defining the Stage in Madagascar

This sets the production in motion, and as we go on, the kingdom is divided more among those who believe traditions and norms can be amended to accommodate an ageing king, while there are those who want to uphold the values.

It is a production that presents characters that flowed in various ways: a king who is afraid of competition and thus has secretly been killing all his would-be heirs before they are three days old to his latest queen, who gets married to him while pregnant with another man.

Golden Calabash puts the audience in a situation where picking sides is as wrong as ignoring everything that is happening.

Of course, the show right there represents modern politics as we know it—a game where people support or hold beliefs for what they stand to benefit. A prime minister that wants the king to mess up, lose confidence and thus gets a chance to aggressively take the throne. A minister of ethics in the production was almost left naked when he tried to stand for the truth; even those who had sworn to support his claim abandoned him. Then there were those who knew the king was ageing and a tyrant but somehow supported him for the sake of stability; they were even willing to do wrong to fulfil his claim.

The show shines the brightest on the choreography, which is a mix of different Ugandan traditional dances and others from African-renowned traditions such as Zulu and Kinyarwanda. It is safe to believe the choice in the dances was to disguise the geography of the kingdom.

See also: John Sibi Okumu: Writing on a Dare!

There were several bold decisions made in the costume department; they never tried to overwork the backclothes and skins that are common with Uganda’s mediaeval stories. The mix of designs and fabrics kept much of the production colourful. It seems Esther Nakaziba, the costume designer, was in a good mood.

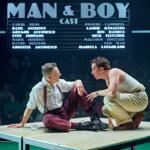

Comedian, Obed (Reign) Lubega and Shamim Mayanja were part of the cast of Golden Calabash (Photos by Kaggwa Andrew)

But above all, the Golden Calabash shines a light on the conversations that art tries to shy away from these days—the politics and dangers of being a pedestrian as things happen. It also sheds light on the topic of sex, with women always being silent when their men are not performing.

The things we learn about the queens are that some of them lived and stayed in the palace for five years without seeing their king, even for a night, but the way they address the topic in a monologue is emotional and gripping. But the most important factor was the fact that they respected the emotions of what women go through when they are not sexually satisfied; they did not play around with them or be comical around the area. It was commendable.

See also: Bwanika Sseremba’s Come Good Rain Finally Comes to Uganda

John Ssegawa’s biggest arsenal was his cast, a mix of standup comedians, comedy duos, and experienced actors, some of whom have graced TV shows such as Prestige, Half London, Honorables, and Sanyu, among others.

These are actors such as Ivan Senjovu, Brian Kalungi, Nodryn Evanci Kabuye, Robert Kasule, Shamim Mayanja, Bruno Sserunkuma, Arinaitwe Ramathan, Obed Lubega, Matovu Ntanda, and Ssegawa.

The show at the National Theatre also doubled as an audiovisual production for the same show; he hopes to take the video version of it to schools and different institutions before he puts on another show.

John Ssegawa’s Golden Calabash is an exciting production, and that strong applause at the end was well-deserved.

This article appeared in The African Theatre Magazine on February 2, 2024, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, please click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kaggwa Andrew Mayiga.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.