The term ‘freak’ thus refers not only to bodies, but also to denormalizing social practices: loafers, being productive but differently, being queer/left/feminist – various practices that for whatever reason did not really lend themselves to any kind of integration into a neoliberal capitalist economy that completely cherished difference.

– Renate Lorenz[1]

Humbaba, a giant with intestines on its face, is the guardian of the Cedar Forest, or the Lands of the Living, as it is known in the epic of Gılgamesh. The epic has several versions – Old Babylonian, Sumerian and Akkadian – and consists of various tablets. It tells the story of the King of Uruk, Gılgamesh. As a result of what we may call a personal crisis in our contemporary era, Gılgamesh decides to go on a journey to maintain his reputation as a successful King with “extraordinary energy, courage, and power,” and searches for immortality.[2] In order to accomplish his goals, the wise (!) King decides to slay the undefeatable demon, Humbaba.

In his book Forests: The Shadow of Civilization, Robert Pogue Harrison asks a very simple yet crucial question when it comes to Gılgamesh’s intentions: “What glory is there in slaying the forest demon?”[3] The writer interprets the character Gılgamesh and his city as an archetype of civilization: “Forests represent the quintessence of what lies beyond the walls of the city, namely the earth in its enduring transcendence. Forests embody another, more ancient law than the law of civilization.”[4] Within the walls of Uruk, history is ready to be written, whereas Cedar Forest is an unknown place where weird characters reside. For Harrison, the severing of Humbaba’s head represents the deforesting of Cedar Mountain. The freak/monster/demon Humbaba living in the depths of darkness, in the land of uncertainties and mystery, becomes normalized by the civilized hero, Gılgamesh, representative of the city, state, and its borders.

In ancient folklore, forests have the potential to provide dream-states that allow for a denormalization to occur; in Jungian psychology, they symbolize the subconscious.[5] They are the “evil antithesis of court or city… a place of wandering and error, in which the straight path is lost.”[6] In this essay, I interpret the Cedar Forest, home of Humbaba, as a black box – a site not unlike clubs like Berghain in Berlin, where three-day-long uninterrupted club sessions take place within a former power plant built between 1953 and 1954. Berghain is a monster-party-machine, enticing all who enter to derail themselves within timeless space that allows for displacement, disorientation, and most importantly, anti-normative practices. Neither “linear-national history” nor “cyclical-domestic time”[7] might occur in such an idiosyncratic space. Contrary to suppressive and controlling perceptions of time of nation or family by entering aforementioned spaces, bodies switch from neoliberal time to a new state/temporality; what José Esteban Munoz calls “ecstatic time.”[8] In ecstatic time, you can “step out of ‘the temporal stronghold” of what Munoz called “straight time,” upon which the existence of neoliberal heteronormative tenets is hinged.

I think of the space of ecstatic time as a black box: a metaphor for performativity that generates darkness and dream-states to shift through dimensions. This black box could be the forest that Harrison talks about when he discusses the domain of Humbaba, the forest freak who falls at the sword of the normative hero: a king, who must defeat a demon from the world beyond the boundaries of his kingdom. Reminiscent of forests, Berghain in Berlin is where the three-day-long club sessions take place with ritual-like experiences, or moments of S&M practices create a hybrid notion of time and space in which queer temporalities are enabled to express themselves beyond a more heteronormative historiography within a literal black box. It could be another time-space, free from the burdens of the outside world, where time fragments overlap, and disconnected times and moments are experienced simultaneously. As Howard Barker writes in Arguments for a Theatre (1997): “Because the box is hidden from the world, it owes as little as it wishes to the world, the rules in the world are different from the rules outside it.”[9]

Although darkness might create fear as well, the obscurity of these black boxes has the potential to trigger various speculations against the suppression of power. It is with this perspective that I will consider Humbaba as a monster in the Mesopotamian sense, in that monsters were neither classed as gods nor demons, but rather described as types of “storms,” for example – “those of the river, of the dry land.”[10] Humbaba’s otherness was encapsulated through nature; itself conceptualized as a dark, magical space.

The Many Temporalities of Humbaba

Humbaba has its reflections on our contemporary world in several ways. According to poet and scholar Sharif Elmusa, the victory of Gılgamesh, his historical immortality, and the building of the city, caused the burden for “the animals, the trees and their custodians” – and though Gılgamesh suffered immensely, “it was the subaltern who perished.”[11] The beheading of Humbaba is a symbol of this death. In some interpretations, the beheading is linked to economic pursuits.[12] Timber from the holy Cedar Forest, as a natural source, was a significant material to construct houses and buildings in The City or Uruk. Reflecting on this history, Elmusa[13] points to George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq for oil as a modern Gılgamesh, making those who have suffered as a direct result of this conquest contemporary Humbabas – dwellers of historical narratives, and multi-temporalities, within a geography that has become a black box itself: a site where narratives manifest in real violence and open conflict. In this regard, the forest where Humbaba resides – this dark cube – is at once a framing in which an othering might indeed occur and a site in which others might exist outside of the frameworks that have been imposed on them.

But nowadays, the Eastern/Southern subject is neither the boy in a Gérôme painting nor a woman from a colonialized land painted in odalisque. However, the rituals of othering continue in various practices. In the interview for Ibraaz Platform 009, “The Performativity of Emotions,” Sarah Abu Abdallah and Abdullah Al-Mutairi indicate the problems around their art practice in relation to stereotyping from a Eurocentric discourse; their forced position as representatives of their region. Synchronic time of middle-class domesticity (Freeman), as well as ceremonies of patrimony and nationhood, have been regurgitated for a long time through various films, books, and other mediums; the movies Stonewall (2015) or 50 Shades of Gray (2015) are good examples of how to whitewash and underutilize queerness and other possibilities beyond heteronormativity.[14] These examples present the black box of the theatre – or mythological narrative – as a site of normalization. For example, when a nation is positioned on an Axis of Evil, it enters into the black site of representation, in that it’s identity has come under attack through a definition deployed over a global stage.

In the book Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology (2015), Michelle M. Wright analyzes the cause and effect framework in relation to Newton’s understanding of time as a result of Enlightenment and problematizes interpellation of Europe “as the vanguard of civilization.”[15] The writer articulates an approach in the book contrary to ‘dominant spacetime’ mentioning what we consider as “known” is racial and discriminative. Wright stresses the fact that time as the fourth dimension in Western science is creating such discrimination: “An object in four-dimensional spacetime can be shown in only four dimensions’, but the fourth dimension is not enough to represent “multiple contemporary moments and multiple past moments in distinct spaces.”[16] In a similar fashion, Tim Stüttgen draws attention to a queer and othered notion of time and space in pop culture, especially Hollywood films, in In a Qu*A*re Time and Place (2014). In the book, Stüttgen points out the fact that the black body, the anti-hero, exists outside the temporality of reproductive and legalized spaces. Apparently, the othered body cannot function in the realms of civilization, which brings us back to the beheading of Humbaba in the Cedar Forest.

Recently, I stumbled upon an image on Reuters depicting a man on stilts with juggling clubs in his hands looking at Hamas militants with weapons. The man belongs to a local circus that performs on the streets of Gaza; the locals, whose city is not visited by circuses, gathered their own circus practicing to be clowns, jugglers or stilt-walkers. They perform a life in another time, focusing on the skills of being a something that serves neither the goals of Israel nor Hamas. Therefore, the encounter between a clown in colourful clothes and a group of militants creates an uncanny sense: who will act first, the soldier, or the misfit? While contemporary Gılgamesh builds the walls around the forest of Gaza, the clowns generate micro-forests in the streets.

In “A Fool’s Discourse: The Buffoonery Syndrome,” Mady Schutzman writes about cultural definitions of femininity in relation to “clownish masquerade of identity.” The fool and her/his bizarre (!) bodily gestures are linked to capitalism: The artist points out that the clown had a voice until the latter part of the nineteenth century. According to Schutzman, the clown lost his voice because “he refuses repetitive mechanicalness” – “he can’t pull it off, can’t manage the simple tasks of hand-eye coordination as dictated by the laws of law, efficiency or discipline.”[17] In this narrative, the anti-normative figure is perceived as headless, because they don’t live according to the rules of society. But this allows for two parallel narratives to co-mingle – that society beheads those it rejects, and those who reject society must necessarily behead themselves.

“Is this what they call civilization?”

… Why is this playhouse in such a mess?

To right-thinking people

it’s a scandal, no less!

But then what makes you go to see a show?

You do it for pleasure –

isn’t that so?

But is the pleasure really so great, after all

if you’re looking just at the stage?

The stage you know,

is only one-third of the hall… [18]

Mayakovsky‘s Mystery-Bouffe: A Heroic, Epic, And Satiric Representation Of Our Era, was originally written as part of the festivities for the 1917 revolution in Russia. The play is ultimately about 11 people who, in a post-apocalyptic world destroyed by all manner of political revolution, find the stage as their so-called promised land. It is “a parable of global meltdown and fracture” that Mayakovsky reworked in 1921, “prefaced with the proviso that” in the future, all persons performing, presenting, reading or publishing Mystery-Bouffe should change the content, making it contemporary, immediate, up-to-the-minute,” as described in the text for Oreet Ashery‘s Party for Freedom (2014) medley – originally a performance, video, and installation project that reinterprets Mystery-Bouffe. The performance starts with a crucial question sung by a repetitive transgressive voice: “Is this what they call civilization?” The question is followed by the Dutch politician Pim Fortuyn’s awkward remarks imagining “the army of Ali Baba” in Europe and speculating on a future, which “guests take over the house.”[19] In the following scene, a naked man wearing a white fake fur repeats the same Islamophobic and discriminative speech as a naked audience clap, recalling a moment he saw a Muslim at a party in London in a terrified tone. The narrative of the king, therefore, belongs to the nationalist; afraid of the presence of outsiders, the “protector” of society craves building new walls and decapitating more heads.

Taking an old theatre piece by Mayakovsky and mixing it with trash aesthetics and technology of twenty-first century, Ashery crosses over time in Party for Freedom in a way that recalls her visualization of gender fluidity in another work, Colored Folks (2001), for which Ashery collaborated with Shaheen Merali in a performance first staged at Toynbee Studios in London, in which Ashery was turned into a black man and Merali a white woman by make-up artist Brixton Bradley. The transformation occurred in a room away from the audience, who watched a live feed projected into another room. Throughout her practice, in fact, we see Ashery transforming into a number of figures, from a rabbit and a Norwegian postman to a fat farmer and an Arab. Aside from performing these identities, Ashery also works with another alter ego: Markus Fischer − an orthodox Jewish man, through which she is able to play with the idea of subject through the production of a hybrid subject whose exists simultaneously within various shifting temporalities precisely because the subject’s identity is predicated on a fabric of narrative fictions; in other words, fantasies, stories, reveries, and dreams.

Adham Hafez Company and HaRaKa platform, 2065 BC, 2015. Multimedia performance and installation. Photo by Nurah Farahat.

One example of transtemporal drag in practice is 2065 BC (2015) by Adham Hafez Company, in which the Berlin Conference of 1884 is restaged. The original conference – also known as the Congo or West Africa Conference – aimed to regulate colonialism in Africa and find a position for Germany among other European countries. The major European countries gathered to formalize the division of Africa. According to some historians, the conference has significance in the history of colonization “which determined in important ways the future of the continent and which continues to have a profound influence on the politics of contemporary Africa.”[21] In Hafez’s new version, it is the year 2065, by reversing the power relations in the world African politicians and scientists gather back in Berlin to claim a new order. The conference starts with the announcement of a female leader: “The conference will begin in one year, two years, three years… 129 years…” From the beginning, time is hauled to an unknown drag-now; a problematic event from history is blended in with a possible future and a new freak moment blossoms into the present as a result.

In the case of Party for Freedom, Ashery takes on Mayakovsky’s original play, and the historical challenge to re-stage it in a way that fits contemporary issues, as a way to enact a rewriting of history through the dragging of time, and the dragging of identities. In order to generate a rhizomatic understanding of history, re-writing and drag are important tactics to mock and transform predetermined roles so often imposed on postcolonial, or non-western identities. Indeed, drag, or more specifically, queer tactics, have offered tools and languages through which to subvert normalization within the performative space of representation itself; or the black box. The drag/clown takes the decapitated head from the floor with pride and turns the existing environment to their forest, a dream-state despite being in the realm of normativity, to dance and generate new performativities.

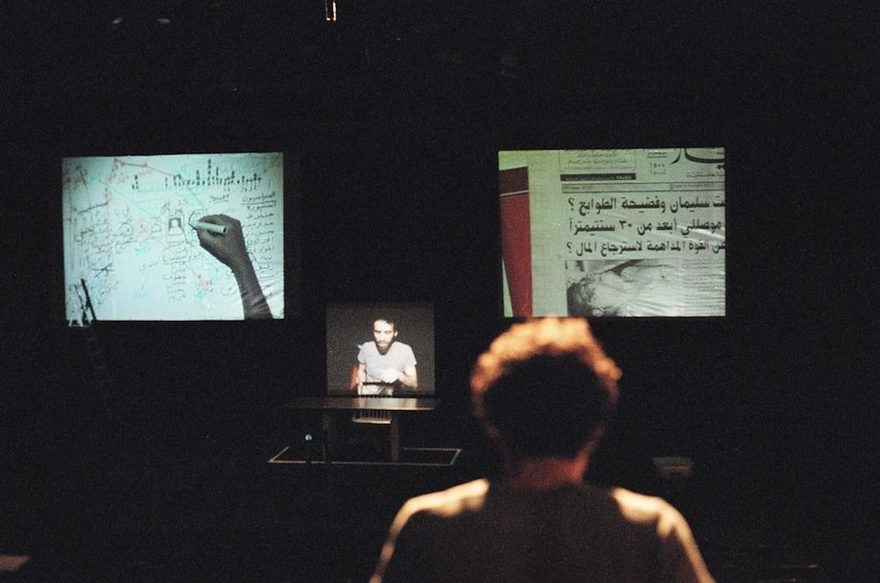

Rabih Mroué, Looking for a Missing Employee, 2003. Ashkal Alwan, Beirut. Photo courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg and Beirut.

Preparations of a So-Called Ending: Why Time and Why Now?

(Re)Writing histories of several temporalities and putting them into circulation is like recycling. Say, if every household separates trash or knows the importance of such a performance, recycling won’t create any tension. In a similar fashion, writing and talking about the stories of othered temporalities or questioning the roles we are expected to perform will create new spaces and time for several possibilities of existence in every household.

In the interview Theatre of The Present, Rabih Mroué talks about micro-narratives, the ambivalent character of memory, and differentiation of timing in theatre, film and video works.[22] In our conversation, the artist talked about how ISIS uses the power of temporalities to stretch an unbearable moment of violence through the videos they publish. To use Mroué’s own words:

“Uploading the videos of beheadings on the Internet is their way of announcing their dreadful deeds. They want to spread their statements through this medium. If the videos were not uploaded then it would be as if the crime did not take place because we are unable to know about it at all. So it is as if it never happened.”[23]

In a way, ISIS uses similar techniques of manipulating time for the benefit of queers, freaks, and othered lives; from their perspective, Gılgamesh must be defeated. As Mroué points out:

“Paradoxically, there are many other things that are happening around us but we are not aware of them. When you don’t know about a certain incident it is as if it doesn’t exist. This philosophy can be applied to the ‘Other’ – if you don’t want to see the ‘Other’ then it will be as if this ‘Other’ does not exist.”[24]

Nation-states pretend that certain bodies or tenets don’t exist at all, and in return, these bodies engage in a performance of visibility – reminiscent of a bad play that keeps touring. One man’s weapon is another actor’s lipstick. So, the space of the video, the black entity, becomes the stage of ISIS that a repetitive re-enactment takes place using the tactics of drag.

Despite not approving of the performance of ISIS, let’s not underestimate the acts of neoliberal nation-states, whose drones have caused teenagers to turn into terrorists. What will happen when the new Humbabas – refugees, people of colour, queers; the ones who cannot keep up with the violence of straight time of any kind of military structure – demand their own schedule to generate unorthodox performances? After the demolition of the forest, what new micro-characters for Gılgamesh to suppress will emerge out of the crisis?

Recently, as a result of digitalization and accelerationism, we have all started to contemplate time in some way or another, and criticize a conception of time that was generated as a result of the Enlightenment, and the colonial violence to which this notion of time is associated. Not long ago in Cappadocia, Turkey, I was talking about Virilio, chronopolitics, and the death of geography with a friend who has a German passport. We were sitting in a restaurant, and approximately 20 minutes later, two locals came and started a conversation about a concept of time in relation to Islam that differs from a modern understanding – related to several temporalities existing at the same time. Just the other day, an academician friend posted an article about Maggie Berg and Barbara Seeber’s new book The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy (2016), in which two academicians complain about frantic timing and demand their time back. Of course, time has always been a preoccupation of sorts for us. In 1962, Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar brilliantly derided the absurdity of time in relation to Turkish modernization in his book Time Regulation Institute, whose protagonist creates an institute to regulate every clock in the country to chase down each second to prevent lifetimes slipping away.

In 2015, before the elections in Turkey, authorities decided to defer the seasonal hour change. The government claimed that it was to eliminate any kind of confusion among the voters that would be caused by the hour change. Regardless of such a decision, some clocks automatically changed the time. The hashtag of the day was #saatkac meaning: “What time is it?” Moreover, whose time is it? Governments know the importance of performative and discursive compulsion to repeat roles, as much as they know of the effect of intervening in such repetition, or conformity, after all. What happened was an example of the absurdity of time and the management around our lives, par excellence. Timing is an important factor in building civilizations, or establishing regimes, after all; the timber that Gılgamesh needed was symbolic of the time and energy the kings of his empire needed to establish and maintain their power. To do so, however, they had to cut off the head of the forest itself, just as a government interfered with standard time in such a way that destabilized the status quo, in a way that one might assume suggests a perspective of the population as a geography that appears as the darkness, or a terrifying forest.

In the Epic of Gılgamesh, Humbaba’s existence is always contingent upon Gılgamesh’s needs, despite his significance. What would have been happened if Humbaba had written about their decapitation in relation to their feelings and thoughts and had created a similar epic? I’d like to imagine the black box, reminiscent of a forest, as a possibility of another time-space, free from the burdens of the outside world, where time fragments overlap, and disconnected moments are experienced simultaneously. This might be Humbaba’s forest – that dream state where Humbabas might re-perform their story by controlling and influencing the temporalities within their own narratives, and rebooting the possibilities of telling such stories. To do this, Humbaba might continue as a beheaded yet powerful other.

Tablet VII

On the way to the Cedar Forest, Gılgamesh awakens from a nightmare. Repetitively, the King has the same dream three times in row: Gods punish Him and Enkidu for killing Humbaba. The dream tells Gılgamesh to leave the Freak of the Forest in peace, however, the mind of civilization desperately longs for fame, power and immortality. Rather than acknowledge the warning, Gılgamesh leaves the dream-state, the other temporality, and continues on his journey to conquer the lands of Humbaba.

[1] R. Lorenz, Queer Art: A Freak Theory (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2012), pp.27-28.

[2] T. Abusch, ‘The Development and Meaning of the Epic of Gılgamesh: An Interpretive Essay’ in Journal of the American Oriental Society 4 (2001): p. 618.

[3] R.P. Harrison, Forests: The Shadow of Civilization (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), p. 17.

[4] Ibid.

[5] C. Addison, ‘Terror, Error or Refugee: Forests in Western Literature’ in Alternation 14.2 (2007): pp. 116-136 http://alternation.ukzn.ac.za/Files/docs/14.2/08%20Addison.pdf

[6] Ibid.

[7] E. Freeman, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), p. 7.

[8] For more information, see: J. E. Munoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: New York University Press, 2009).

[9] H. Barker, Arguments for a Theatre (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997), p. 74.

[10] S. Elmusa, ‘The Ax of Gılgamesh: Splitting Nature and Culture,’ in Culture and the Natural Environment: Ancient and Modern Middle Eastern Texts, ed. S. Elmusa (Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2003), p. 42.

[11] Ibid., p. 47.

[12] T. Sedlacek, Economics of Good and Evil: The Quest for Economic Meaning From Gılgamesh to Wall Street (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), pp. 24-25; and D. Damrosch, Buried Book: The Loss and Rediscovery of the Great Epic of Gılgamesh (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2006), pp. 265-266.

[13] Damrosch, op cit., p. 266.

[14] For instance, although the legendary Stonewall riots against the oppositions towards homosexuals were instigated by a transgender woman of colour named Marsha ‘Pay It To No Mind’ Johnson, in the film a young white cis man is the protagonist as the queer activist. In the case of the movie 50 Shades of Gray, S&M is depicted by a billionaire man and his assistant, two typical characters of Hollywood in terms of body and social codes. In the trailer, where important scenes are highlighted, two conversations get the attention. First, the woman asks the man to enlighten her; the man in power, the mind enlightening the wild young body. And in the second, the female answers to the question ‘Where have you been?’ posed by the male by saying she has been ‘waiting.’

[15] M.M. Wright, Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), p.40.

[16] Ibid., p. 60.

[17] M. Schutzman, ‘A Fool’s Discourse: The Buffoonery Syndrome,’ in The Ends of Performance, eds. P. Phelan and J. Lane (New York: New York University Press, 1998), p. 143.

[18] From Vladimir Mayakovsky’s introduction to his Mystery-Bouffe: A Heroic, Epic, And Satiric Representation Of Our Era, taken from an interview: N. Budzinski and O. Ashery, ‘Unfinished revolutions: Oreet Ashery’s Party for Freedom,’ The Wire, March 2014, http://www.thewire.co.uk/in-writing/interviews/oreet-ashery_s-party-for-freedom.

[19] From Oreet Ashery’s Party For Freedom medley, https://vimeo.com/87743423.

[20] S. Halajian, ‘The Personal and the Political All at Once: Adham Hafez in Conversation with Suzy Halajian,’ Ibraaz, 25 February 2016 http://www.ibraaz.org/interviews/182/.

[21] Craven quoting Tony Anghie: M. Craven, ‘Between Law and History: The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, and The Logic of Free Trade’ in London Review of International Law 3.1 (2015): pp. 31-59 http://lril.oxfordjournals.org/content/3/1/31.full.

[22] G. Kunak, ‘Theatre of the Present: Rabih Mroué in conversation with Göksu Kunak’, Ibraaz, 28 May 2015, http://www.ibraaz.org/interviews/167.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

This article was first published on www.ibraaz.org. Reposted with permission of the publisher. Read the original here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Göksu Kunak.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.