Though theatrical season 2020/2021 isn’t the most eventful, it has brought to the stage number of remarkable stagings, with several interpretations of a classic Shakespeare play to become extremely topical.

Back in autumn 2019, a stage directing laboratory under the supervision of Danny Mayfer took place in Minsk within the International Theatrical Art Forum TEART. Six Belarusian directors worked on Shakespeare’s Richard III play. Two of them – Alexander Yanushkevich and Elizaveta Mashkovich should present their stagings to the audience as full-fledged performances in the early spring of 2020. However, due to the pandemic, the premieres were postponed, and the forced delay gave Shakespeare’s classic an unexpected contemporary relevance.

From July 2020 to the end of the year, four interpretations of the play appeared on independent venues and stages of private theatres: AVE, Richard by Elizaveta Mashkovich (Chamber Drama Theatre / Natalia Bashava’s Theatre Workshop), Richard by Maria Tanina (Visual and performing arts center Art Corporation on the Ok16 cultural hub’s stage), R3 by Alexander Yanushkevich (Visual and performing arts center Art Corporation on the Ok16 cultural hub’s stage), Richard 3 by Elena Medyakova (Contemporary Art Theatre).

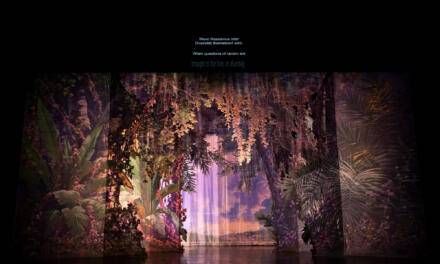

Photo courtesy of Elizaveta Mashkovich.

Each of the stage productions revealed the distinctive ways of this classic’s interpretation made by modern directors both at the level of working with the text and in the solution of the staging’s forms, which needless to say varied greatly. Alexander Yanushkevich’s performance that was focusing on acting and the visual solution (costume designer Tatiana Nersisyan, lighting designer Ilya Gusev) was all about asceticism, while Alena Ivanyushenko’s adaptation of the play included several explanations about the characters and events, while Tanina’s staging emphasized on the digital technologies use (digital artist Alexander Nuvo). The topicality of the sound was common to all productions, regardless of the chosen form. It was even more noticeable in the first performance of the Richard series, AVE, Richard by Elizaveta Mashkovich, shown at the Chamber Drama Theatre in July 2020.

While preserving Shakespearean plot, Elizaveta Mashkovich covered the old story of a fight for power with present-day realities. In Mashkovich’s stage show the future king uses “eavesdropping” to know about the moods and plans of his political rivals, reaches the signing of the necessary papers by the means of tortures while treating his nephew with potassium cyanide. And the most loyal helpers and advisers in his crimes are not living people, but Siri and Google.

Instead of the gloomy vaults of medieval castles, the political playground was transferred to a desk that was turned by the play’s set designer Alexander Adamov into a place for Richard’s manipulations. The victims of his intrigues are literally made as toys in Duke of Gloucester’s hands. The props and most of the characters are replaced by ready-made objects and silent puppets, dialogues’ sound recordings, and the screen to which live images from Richard’s phone are transmitted. Faceless and voiceless victims, enemies, and even Gloucester’s allies create a background for the single hero (antihero to be correct) performed by Nikita Chabatar, whose figure dominates in the play’s space.

The form of a chamber solo performance highlights Shakespeare’s focus on the central villain-genius character. Nikita Chabatar’s Richard is a young handsome man who factitiously imitates the bodily deformity time after time because the appearance as an external image of nature is a thing of the past.

Photo courtesy of Elizaveta Mashkovich.

Contemporary Richard has inborn immorality rather than a hump or ugly face. The mention of a puppy killed in his childhood points to the natural villainy of the character. There’s an image of a villain-politician of a new type in the staging: his intrigues and actions are much less refined than in Shakespeare’s original, his lies and gossips are shown as the cheapest “all balls no whistles” level ones. “The world is ruled by power, and I am the power,” says contemporary Richard. He is satisfied with violent manipulation rather than cunning intrigues. And the audience hear loud “Ave, Richard!” out of his gadget’s speaker.

Elizaveta Mashkovich manages to turn a bloody chronicle into a play that resembles a Hollywood action movie. It looks interesting and easy because everything that happens on the stage is a game, but you can’t call it funny. Though the staging is done very skillfully, sometimes it seems to be a collection of techniques that have turned into a “contemporary play” toolkit, which includes rewriting the classics on a modern basis, reading the text from the gadget’s screen, live music (musician Ivan Mashkarov), interaction with the audience, and digitalization of the performance. However, the use of all these tools can’t be called a disadvantage. Thus is the contemporary theatre’s language that the director uses successfully. The use of gadgets and their capabilities, various masks, and effects of social networks and messengers doesn’t hurt the eye, because this is not just a trendy trick, but a tribute to our life, in which the Internet is a way of communication, self-presentation, and public opinion formation. Moreover, the phone and the web in the play are a world of reality constructed by Richard, his perception and the total loneliness of a man who decided to play a tyrant because he has no other passion and purpose in life than power.

Much sadder is that for all the richness of the meta-form of modernity and the topicality of images, the play lacks depth, including the depth of the protagonist. How will Richard’s game end? Will the whispers of the victims about Richard’s crimes and the voice of his conscious visualized by the flashing red “Guilty” word on the screen make him stop and back off? The ending is ambiguous and hidden in the dark.

Translation: Alexander Mantush

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Katerina Eremina.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.