Thomas Irmer is a scholar, dramaturg, and critic regularly contributing to Theater der Zeit, Theater Heute, and Shakespeare (Norway). He has also worked for various international festivals, including spielzeit Europa/Berliner Festspiele as a dramaturg from 2003 to 2006. His recent books include Andrzej Wirth. Flucht nach vorn. Erzählte Autobiographie und Materialien (2013) and Maria Steinfeldt. Das Bild des Theaters (2015). His recent academic research covered the new phenomenon of the internationalization of German theater, and he taught a class on this subject at the University of Osnabrück from 2014 to 2015. He has also made documentary films on theatre and theatre history, among them the prize-winning The Staged Republic – Theatre in the G.D.R. (2004). He lives in Berlin.

Ivanka Apostolova Baskar: Outside of COVID-19, is there a real need for the evolution of internationalization in theatre, or it is a kind of theatrical engineering by cultural politicians? Does this model have anything to do with the politics of globalists and their limited vision of culture and art versus the money and power, or not?

Thomas Irmer: The internationalization of theatre, as we have seen since the 1990s, has been driven by several aspects. One was a certain utopian idea that international exchange will help intercultural exchange on all artistic levels. Before 1990, the international theatre was much more exotic in the sense that you would see one outstanding production from another country as an exception, like something in the Olympic games. But then, the international exchange became much more common, and it was no longer restricted to a few handpicked, outstanding productions. Instead, a whole field of complex relations within theatre culture emerged. In the 1990s, new festivals were founded that showed productions on a large scale, which were often followed by an invitation to a foreign director or the growing interest in drama from foreign countries, to name a few examples.

The other part of your question, whether internationalization is more money-driven, can be easily denied. In most cases, festivals can be costly and big money machines but in the end, they only break even after the last performance. They still have to be subsidized. In that sense, the internationalization of theatre has been mainly an investment for theater, audiences, artists, and culture, not a profit-making enterprise. So if you compare it with other forms of cultural events, like pop music, you will find that this phenomenon cannot be seen as profitable for international markets.

IAB: How ready are the artists in Germany and Europe to internationalize their theatres and working processes, and to collaborate with someone from a completely different method, technique, tradition, way of working with collective, working conditions, with different ideas about self-censorship or censorship in art, local politics, and so on? More precisely, how is internationalization conceived? How should it be implemented and accepted? Will someone mentor or instruct us, or just inspire and guide us?

TI: I think there is no general guideline for this. One fundamental point, of course, is that contemporary theatre in Europe has been fueled by different international influences for a long time. Think of ancient Greek culture, then of the golden eras in England, Spain, and France in the 16th and 17th centuries, or more recently – what British and American drama meant for the rest of Europe after WWII. So there is a historical layer that helps us understand this phenomenon’s foundations.

But this is what theatre models used to be, and drama from the past has become a much more up-to-date mode of inspiration for theatre forms and ideas. It is because of how theatrical communication works within the culture that we often see similar economic and political problems while seeking aesthetic innovation. A good example would be how Berlin Schaubühne started international collaborations, developed its very own festival FIND (Festival of International New Drama), imported various directors for their repertory, and so forth. Of course, this was successful but it also made them very vulnerable now, as the international exchange has basically stopped.

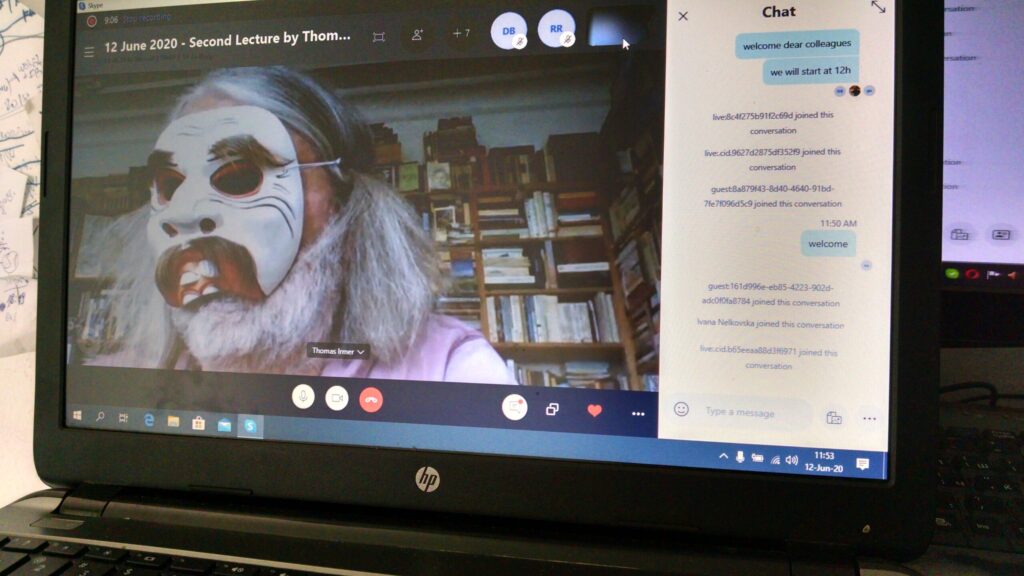

Mr. Irmer is wearing a traditional theater Bali mask (apropos COVID-19). Photo credit: Ivanka Apostolova Baskar.

IAB: To what extent did COVID-19 put the internationalization of theatre to a digital test, or did it disable and temporarily stop the process? And are these new ideas more advanced than the older dynamics of reality and their realization in life, theater, and the performing arts?

TI: Festivals have avoided streaming international programs, but this may be explained by copyright and local law. This is unlike national festivals, like Berlin’s Theatertreffen for German-speaking countries, which have used streaming to save the festival. The most visible problem is still the lack of good and functional aesthetics for digital outlets.

IAB: Thomas, you say that you see the future of avant-garde in the creation of youth plays. Youth theatre has the potential for fresh ideas and ingenuity because of young people’s sensory and hormonal agony, home life and education, or their action/reaction to the times in which they are consciously-unconscious co-creators of some new artistic needs and dynamics. Also, young people can be “dangerous” copycats.

TI: What I meant was that theatre (as a culture) should not neglect theatre for young audiences, as they are the future. There are two things needed to maintain quality in this field. The first is that children’s drama should be as good as plays for grown-ups and may be written by the same authors. The second is that one should apply the same aesthetics from regular theatre to children’s theatre. This simply means that directors or companies could be invited to make work for children. What is important is the maintaining of quality and ambition, which is often overlooked and treated as less important.

IAB: Many established artists fear that younger generations will oust them from the stage, and believe that non-profit art and culture were rapidly ceded to women and young people without solving any problems related to generation and age gaps. Or they believe young people automatically possess an intensity and enthusiasm – key features for creating top theatre, dance, and performance – which creates a tendency to infantilize art and culture. Or they think the culture budget can easily be reduced if culture is dominated by young people who seek meaning, and they have the energy to survive on less money.

TI: The confrontation between younger generations and old masters defending themselves against young rebels is nothing new at all, and keeps repeating itself over and over again. What can be special in a given situation, as is observed in many Eastern European theatre cultures, is that the advantage the old masters have is based on their institutional power. There is little counterbalance from outside institutions. This can become stifling for innovation – tradition is not a road to the future.

IAB: Today, every director’s dream is to be able to work in German contemporary theater due to working conditions that do not exist in other countries across Europe, like big budgets, tolerance for different modes of theatrical expression, professionalism, major festivals, stable businesses, and good programming criteria. How have people from the national, local, private, and alternative stages set themselves up during COVID-19, and what are your predictions for the future of theater, in terms of dramatic texts and direction?

TI: From Monday, November 2nd, all theatres are closed again at least for the rest of the month. This is a result of a decision by the prime ministers of the German states and chancellor Angela Merkel. The fight against increasing cases of Coronavirus in Germany includes drastic measures in the field of culture. Museums, cinemas, concert halls, exhibition venues, and theaters must close again.

Almost everybody in the field of culture agreed with the first lockdown in spring that lasted, for many, well into summer. In late August most theatres resumed work with increased safety measures and social distancing. The season started with reduced seating and sometimes-absurd entrance policies, and people were required to wear masks in smaller venues. But it worked and proved that theater was possible during the pandemic.

However, the first reactions to the second lockdown are quite different. The main argument made by artistic directors and other administrators is that theatres have carefully prepared in order to meet all regulations, and no spreading incident has been documented in German theaters and opera houses. Therefore the closing of all theaters is seen as unjustified, and even unjust when compared with less safe places like public transport or shopping malls. The first protest was launched in a joint statement from all of the Munich theaters and opera houses while the chancellor and prime ministers were negotiating their pandemic plans on Thursday.

A debate about the value of culture, in general, underlies the first protest. There may be the “Check on Culture” policy in every country now, where culture is not regarded as a profession in times of crisis. The second lockdown seems to prove that culture is of no priority to the government even though it was given reassurance in spring. Moreover, the existence of even well-subsidized theatres, not to mention the much more vulnerable independent companies, is now at stake. They all just started to recuperate from the first crisis and anticipated huge losses at the box office this season. Now, they have to start rethinking what their efforts were worth and if they were meaningful within German culture. Much dissent will be heard in the coming days, like that already shared by Ulrich Matthes, star actor of Deutsches Theater and president of the German film academy. Also, the Berlin Academy of Arts demanded: “such measures must be more differentiated.” German culture is in a state of unrest, and rightly so.

Photo credit: Ivanka Apostolova Baskar.

IAB: Do you believe in the complete collectivization of art? Co-creativity and collaboration ease workloads and stress but is there a long-term perspective given the unpredictability of the ego, and vanity and narcissism of the individual, versus responsibility and co-responsibility?

TI: Theatre has been collectivized from the beginning. The question is about the hierarchies in the making process and in running institutions. Please allow my aphoristic joke as an answer:

Who is the most important figure in the theatre in each respective century?

18th century? The playwright. They are central to the development of modern theater.

19th century? The actor. Think of the great touring star actors – people came to see them, not Macbeth.

20th century? The director, from Max Reinhardt to Frank Castorf or Robert Wilson.

21st century? The producer. Think about it – there’s been a shift from the artistic process to new forms of organization.

IAB: There is an interesting saying that today all roads lead to Berlin, especially for people who create contemporary art and theatre, and work in contemporary cultural management. It is a metropolis with a really open spirit but also a lot of problems as a side effect of openness. You have an interesting view on the myth of the Berlin scene versus the artistic power of the theatrical stages off-Berlin and off off-Berlin.

TI: I think Berlin is overrated as the one single city where it happens. It is still a great center for theatre but certainly not the only one in Europe. Maybe the COVID-19 crisis will reshape much of it as the theatre will revert to being more basic, more local, and more direct – even when streamed all over the world.

IAB: On festival culture – is this year on standby or does it continue online? This is contradictory because despite all the pressures due to COVID-19 people do not give up so easily. They perform digitally despite nostalgia for the standard relationship between stage artists and live audiences. However, what do you think about the future of festivals in Germany and around the world?

TI: It is too early to make a comprehensive judgment. But for sure, the financial consequences for international theatre and their festivals caused by COVID-19 will be severe and long-lasting. In a way, we lost the three decades over which we developed our understanding of international theatre. But it does not mean that it will disappear altogether.

IAB: Dear Thomas, thank you very much for your trust and collaboration.

Skopje/Berlin, 2020

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ivanka Apostolova Baskar.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.