A connoisseur of new art forms and emergent technology, Lance Weiler is a highly sought-after storyteller and media artist practicing in film, TV, theatre, games, and code. After stunning audiences of Hollywood in October 1998 with the astonishing horror film, The Last Broadcast—the first all-digital release of a motion picture—the thought leader once again brings his distinctive vision to Columbia University School of the Arts where he is Associate Professor of Film and Theatre and since 2013 the Founding Director of the illustrious Digital Storytelling Lab.

An International Emmy-Award-winning writer, director, and producer, Weiler leads the lab’s engagements and facilitates its pioneering vision. Utilizing the virtual world, live experiences, and interwoven media, Weiler fuses storytelling and technology in remarkable new ways.

“In terms of the forms and functions as I mentioned before. We explore those at the lab. Basically the way that we explore them is when we say forms we mean emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, virtual reality, augmented reality, and decentralized technologies like the Blockchain and so forth and on. And and when we say functions, we mean that we can harness storytelling as a tool for learning and for healing and for entertainment and for policy change, things of that nature,” said Weiler.

By means of a blossoming series of activations and experiences both online and off, Weiler zeroes in on the lab’s DNA and what makes a powerful story, revealing its methodologies and creative frameworks:

“In terms of the way that we approach those forms and functions we use a number of design principles to help us build the various experiences that we make. And I do this in my own practice as well. Those principles are as follows. The first is this idea of a Thematic Frame. And I should note that these principles come from years of kind of running large participatory type of experiences. Those that radically shift the ownership and authorship of stories and empower those formally known as the audience and enable them to be part of the world in a meaningful way sometimes as much as becoming co-conspirators or storytellers in their own right within the framework that we establish, right? Within the project itself dependent upon if it is a project that embraces that and al lot of the lab projects do and a number of projects that I work on do as well.”

He continued, adding:

“When we say blank space I’m going to lay out first the design principles because they’ll help to demonstrate what I mean by blank space. The first is this notion—and I should say these design principles come from running many many different types of experiences all over the world so this is something that we found through trial and error, a lot of experimentation. So the first is the idea of a Thematic Frame. When you have a thematic frame it creates a common kind of grammar. And it allows people to be participatory and collaborative very quickly and it gives them the language that enables them to collaborate in a meaningful way with each other, right?”

“The second is this notion of The Trace. We found from running these experiences that if you leave room for people to be able to see some trace of themselves within the experience that you have created. And when I say experience I’m talking about immersive theatre works that are participatory. I’m talking about things that are interactive in nature that could be that are mashing up like gaming and theatre, and cinema.And so the idea of The Trace is when people participate, can they see some little piece of themselves within the experience? And when they do, the engagement level goes much higher.”

“The third is this idea of Granting Agency. We live in a time where it’s moved from a one-to-many paradigm into a many-to-many paradigm. And that presents interesting challenges in terms of how you design or craft these worlds. And when I say worlds I mean these kind of experiences. Because now you have to take into consideration you know the agency of one versus the agency of many. When do you allow someone to have agency within an experience? And do they have it as an individual? Or do they have it when they are paired with somebody? Or do they have it when they’re in a group of people? And understanding the balance in terms of personalities and dynamics and what people are comfortable with there’s a whole interesting design process to the way in which you bring agency to the work,” said Weiler.

Prompting us to seek elements of chance as an instrument, Weiler continued, adding:

“And the last is this idea of Serendipity Management and I would say that a lot of digital experiences are over designed. They are so afraid that someone is going to break them that they don’t leave room for people just to bump into each other for amazing things just to happen. And so when we say blank space, we are talking about can you put in place the elements that will allow people to bump into each other and to discover things unexpectedly? And part of that blank space comes from you relinquishing some degree of control and the other part of it comes from you really on the other side of it designing in a way that keeps in mind something that it is going to grant that agency is going to allow for people to see a trace of themselves and is anchored very much in a theme. And so when you get to that idea of the blank space, it’s like did we leave room in what we were doing to allow people to go to maybe places that we didn’t intend? I love that serendipity part because it creates almost like this magical and enchanting element. Where as when you are creator, I feel like as a creative work or co-creative work, I want of be learning and discovering things and I want the process to be magic too, right? And so I think by leaving that space and allowing things just happen and I think in theater, you know? Theatre is very much like ‘the show must go on; it can never break; we never let them see the seams.’ And I think a lot of what we’re doing in terms of that idea of blank space is a challenging concept, right? We’re sitting at the edge of highly participatory culture right now where anybody is a storyteller and people are really super engaged in making things, consuming those things, altering what those things are, remixing them, sharing them and so forth and so on. So that role of audience as I was mentioning is really shifting. So what does that mean in terms of making work? When I say all of that, the audience isn’t writing the story per se. In the case of Where There’s Smoke, there is a core narrative that is really well-crafted within the center of what the experience is. It’s emotionally resonant. it has has very crafted kind of beats and acts within it. But It leaves rooms for moments of discovery. For moments where participants are uncovering things. And because it is designed in a way that it is happening concurrently it has more aligned with you see with massive online multiplayer games.”

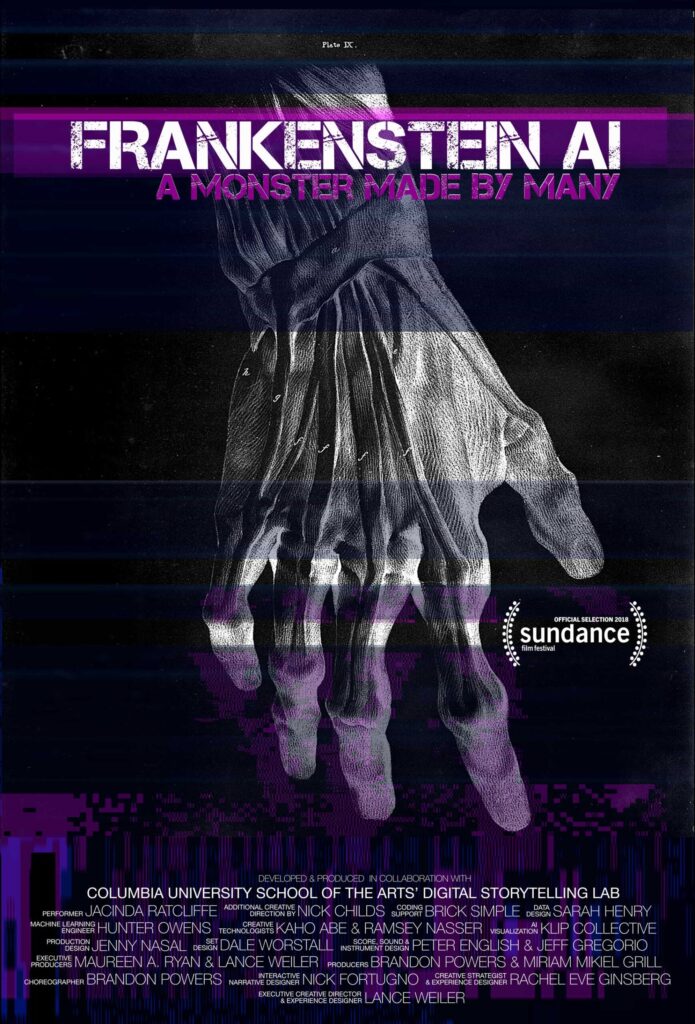

Frankenstein AI. Image courtesy: Digital Storytelling Lab, Columbia University School of the Arts.

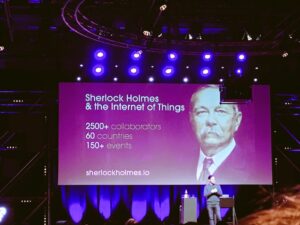

Marked by masterworks that encourage cross-disciplinary collaboration and experimentation, Frankenstein AI: a Monster Made by Many and Sherlock Holmes & the Internet of Things are ongoing prototypes developed and run by Columbia DSL. The projects delve into humankind’s relationship to the all-embracing and advancing technology that is artificial intelligence.

“Because Frankenstein AI was this retelling of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. It was inspired by the book and we did it the same year as the 200th anniversary of Shelley’s seminal novel. What was interesting about that is the narrative that Frankenstein’s monster is kind of wandering the Internet in search of what it means to be human and is confused by what it finds. You know? It finds extreme polarization and toxicity, and hate and love, and it can’t make sense of it and so it determines that it’s going to assemble humans in the real world to help it understand what it means to be human. And so it flips the script. And normally the way we think about artificial intelligence is it’s like a personal assistant that we have on our phones for instance. That’s the most common way that people interact with it on a daily basis. But you know we’re lucky if it understands us and if it gives us the results that we are searching for. So we just thought it would be interesting to just flip that. What if the machine was questioning us about what it means to be human?”

Frankenstein AI: a Monster Made by Many at Sundance. Photo courtesy Columbia School of the Arts Digital Storytelling Lab.

One to dazzle audiences with ingenuity and originality, Weiler spells out the power of the prompt.

“We created a chat bot that wrote in Shelley prose, trained it off of Shelley’s core text and the corpus that we used harnessed data from the Internet and a variety of data sets that we felt would be interesting to explore and then we built out a series of questions. So the machine created the questions that humans would then answer. At the core of that piece is the power of the prompt; the power of question. And that it embraces this notion of ‘yes and’, which is very familiar to your readership. This idea that the moment you say ‘no’ or ‘but’ you kill the scene right? And so, Frankenstein AI is really rooted in this idea of the other. It is rooted in this idea of isolation and connection. And ultimately rooted in this theme of what happens if something we create gets out of control? And that becomes a wonderful universal theme and very relevant for artificial intelligence, right? So at the core of Frankenstein AI and Sherlock Holmes and the Internet of Things is literature. And there’s a reason that we tend to use public domain works. It it it allows us to create a collaborative environment where we are not entangled by intellectual property.”

Sherlock Holmes and IoT. Photo courtesy: Columbia University School of the Arts.

On the theme that plays up Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, Weiler continued, adding:

“What if we were able to use narrative deduction to examine these new emerging technologies like the Internet of Things, which is kind of this idea that every day objects become connected to networks and they can become smart in some way. What if we use narrative deduction to better understand what the core technology was. And what if we used Arthur Conan Doyle’s literature as kind of a jumping off point to create a massive connected crime scene with people all over the world? What if we allowed them to create these artifacts that resided within a crime scene and the artifacts? What kind of adaptations or elements that were found as part of Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories but were adapted for the current time or they were set the past or they were set in the future.”

Sherlock Holmes & the Internet of Things. talk with Lance Weiler. Photo courtesy: Columbia University School of the Arts’ DSL.

As a consequence of inviting the public into a process, today’s creators and collaborators shake up routines and satisfy curiosities by seamlessly integrating offline and online experiences.

“At the heart of lot of the work that we do is the notion of discursive design, which is this idea that you kind of build worlds or artifacts that are intended to allow you to suspend very similar cinema. To allow you to kind a get lost with in the moment that you find yourself in. Hopefully, right if it’s working. And then in doing so leads to really interesting and dynamic conversations and potentially shifts of perspectives that maybe for some could be could be transformative, which would be amazing. We try to do immersive learning experiences. That’s what we design. Sherlock Holmes & the Internet of Things had teams of people over 26 hundred participants around the world from 60 different countries creating these artifacts and the artifacts might be you know one group did an AR and augmented reality app around food waste in São Paulo. And it combined that with storytelling. We build creative frameworks that encourage people to be creative and to be storytellers in their own right within them. Add to help co create worlds that ignite the imagination of many. They are often related to some impossible problem, you know? And that allows for exploration of that problem through storytelling,” said Weiler.

Sherlock Holmes and IoT. Photo courtesy: Digital Storytelling Lab at Columbia.

Grasping a slippery notion, such as the creative renaissance around Blockchain, Weiler turns his lens on decentralized tech as a utility and as a creative expression:

“We are working on new one that will premier in October that’s a blockchain fairytale project where a group of people come together and we were kind of looking at this notion of mythmaking and folklore and kind of leaning into this idea of indigenous cultures and how they would tell a story and the goal was to try to have the story last seven generations and how a lot of those stories were transmedial and and how a lot of oral traditions had people embellishing each other’s and adding to stories and they were eventually codified when someone wrote them down, right? So in that project, we’re basically saying that what if you walked into a film festival and the film that you were going to see you actually shaped, right? It came from stories and experiences you were having in that room and it became reflected back to you. What would that be like right? That’s a totally different paradigm. Normally you walk in and the film is done. To your point, It raises really interesting questions for the longest time, in film and theater, those forms and even games—the art is evaluated based upon the final result, right? The idea of the film, the play, the game, right? But what the iteration and when you’re involved with participatory work, the iteration itself is very much a part of the art form and it’s not just about evaluating what is the end result. It’s kind of like that old adage, right? It’s not about the destination, it’s the journey. And so i think in that respect we’re just experimenting with this ever shifting visual landscape and how it impacts the way in which stories are told, how they are sold, and what the underpinnings and the purpose of them a can be—and that is really at the heart of what trying to do,” said Weiler.

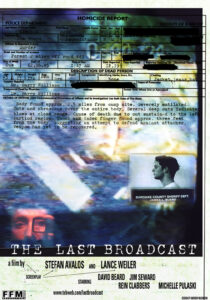

Re-inventing entertainment is a theme that plays out in Weiler’s oeuvre. The story behind The Last Broadcast, which Weiler co-wrote, co-produced, and co-directed with Stefan Avalos raised the eyes and the heartbeats of the Hollywood elite. At that time the project represented the future of cinema. Weiler introduced the distribution methods in 1998 that has since become the standard for digital cinema today.

“The Last Broadcast is really interesting because i think in some ways If I would have known what it was going to take to do it at the start, I probably wouldn’t have done it In the sense that it was so much work. But that’s the beauty of it right? I think the quality of what makes it work and this is something that I try to have in my every day practices is a sense of curiosity and a healthy dose of being willing to be naïve in certain respects, right? Because what it did was it allowed us to, we didn’t know what couldn’t do. We didn’t know the rules. Because we didn’t know the rules and because we had made the movie for so little. Because the movie really came out at this moment of breaking from permission-based culture. I had tried to raise money for a sci-fi film; it failed miserably. My co-writer, co-director, co-producer, Stefan Avalos. He had been ripped off by a foreign sales agent. We had found ourselves in this situation where the system wasn’t necessarily working. And so I had finished up a music video one night working in New York and I was waiting for a train and I was at a newsstand and I saw a video magazine that had an ad for a piece of hardware and card that you could put into computer and you know it would allow you to edit at home and I thought, oh man I need to get a computer. And so, Stephan and I went off and we started building our own computers and we ended up making The Last Broadcast, we tried to make it for no money. We wrote with folks that we knew in mind, family and friends to play the parts. We played parts because we knew we would be there. We knew we would show up. And then we constructed around these constraints a variety of different things. The core of the emerging technology of that time, which was digital was just starting. We started making it in 1996, 97 and then ended up subsequently releasing it 1998,” said Weiler.

The Last Broadcast poster. Image courtesy: Lance Weiler.

As the first all-digital release of a motion picture to theaters via satellite, The Last Broadcast was made for $900 dollars and went on to become a box-office success, grossing over $5 million dollars.

“When we total up all of the receipts, we realized that we failed—we didn’t make it for no money we actually made it for $900. And in doing that i think you’d be hard-pressed in that year of 1998 to find a line item in Titanic, which was the largest film at that time that was $900, right? So we ended up making it and we could have basically just buried in the backyard, right? We were totally liberated by the lack of funds that we had. It made us really creatively resourceful. And because we didn’t know what we couldn’t do. It emboldened us to just to experiment and try really anything. And because we did that and because we had the experiences before negatively with the raising of the funds and Stefan being ripped off, we were really like we kind of know what that side is like, why don’t we just try new things to see what happens? And so we just became experimental. And so when we finished the movie, which we made for $900 it was time to take it out on this festival circuit. At the same time I read about a company called Digital Light Processing, which was innovating these new chips that were revolutionizing projection. And I thought wow, they were releasing them to a number of OEMs, original equipment manufacturers—Barco and Sony and NEC—and I thought well I’m gonna write to those companies and see if they want to be a part of the showing of The Last Broadcast because it could be the first all digital release of a motion picture that’s representing the future of cinema. So I sent these letters that’s how long ago it was—It was all snail mail. And nobody responds after I send them. Meanwhile the computers are rendering away. It took at 86 days to render the movie. As we were getting closer we really just didn’t want to be in a situation where we would have an issue where we would have to show on a poor quality projection like LCD projectors at the time were really poor quality. So I was struck at a point and I thought what if I sent the letter to one of the companies but I purposely miss addressed it, you know? So they know that I was talking to multiple parties, what would happen? Because we had nothing to lose we were really just kind of bold and so we sent out all the letters and after nobody responded then all of a sudden all of the companies responded. And then we ended up with projection anywhere in the world that we wanted for over two years.”

As Weiler moved forward, courageous choices were necessary.

“We started taking those projectors everywhere taking them to festivals. We introduced them to Cannes and Sundance. But it was interesting because Barry Rebo, who is a colleague and works in the industry. He told me at one point that ‘the West is riddled with pioneers with arrows in their backs’ right? And there was this element when we were first showing the work and democratizing the process of making the work that fellow filmmakers were not happy with us. Certain ones were, they were like: ‘this isn’t film, you’re not shooting on film, so you’re not a filmmaker,” said Weiler.

All about the big picture, Weiler’s message is to bring awareness to the possibilities around creativity—the key to a successful endeavor.

“Now flash forward. We ended up helping to innovate what became the first all digital release of a motion picture, which is how cinema is delivered primarily today. So we did that without any resources until we connected and talked our way through two different satellite companies and pitted them against each other and walked away with like 2 1/2 million dollars to R&D what would become digital cinema. And so I think over and over again what I learned from that epiphany moment was that the storytelling wasn’t just about what we are writing on the page. The whole thing was the storytelling; it was all about storytelling, right? Storytelling in a way that will help people want to become part of a vision to want to come and work on a no budget movie. Storytelling to be part of a vision to allow folks to see the potential of what cinema could be in the future. And just like over and over again, storytelling was our super power in a certain way because we didn’t have money to throw at problems, we just became more creative. Because we had made the movie for so little, we were freed by that. So when I think I look back on it, the movie is this really interesting time capsule of the mid to late 90s,” affirmed Weiler.

Employing the increasingly beautiful medium that is technology and subject matter that push and pull at edges of artistic expressiveness and narrative, Weiler who sits on steering committees at the World Economic Forum explores questions of synthesis and the potentials of the human spirit:

“At the core of what we do is interrogate technology so humanity can have a seat at the table to basically say how can humanity help to shape technology before technology shapes us,” expounded Weiler.

When it comes to the future of content creation framed by additional perspectives and voices—namely cinematic gaming innovations and experiments that play out across film, TV, theatre, AI, mobile, and web—Lance Weiler is someone who enthusiastically seeks out new experiences and offers up possibilities to embrace them.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alexander Fatouros.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.