Professor S.E. Gontarski is the honorary patron of Beckett Research Group in Gdańsk, created and directed by Professor Tomasz Wiśniewski. BRGiG is the organizer of The University of Gdańsk Samuel Beckett Seminars that have been held every year since 2010. They have been attended by scholars and artists from various parts of the world and have resulted in several publications and film documentaries. Guest speakers have included: Enoch Brater, H. Porter Abbott, Derek Attridge, Nadia Kamel, and Mark Nixon. Various forms of workshops have been offered by: Marcello Magni, Douglas Rintoul, Nicholas Johnson, Jonathan Heron, Robson Corrêa de Camargo and Patricio Orozco.

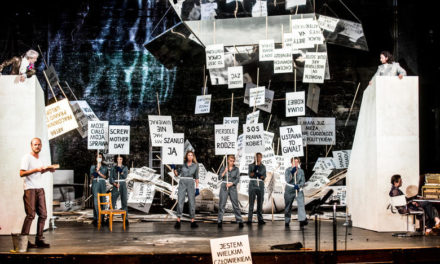

Kosmopolis designates a space of creative energy, a site for knowledge exchange through literature and performances without borders, where texts are less in conflict with performance than where they synchronize, where discourse and the embodied arts are not at odds or in conflict, where words and images, transmitted on paper, canvas or embodied, resound toward new possibilities, new visions, new beginnings. It is an unrestricted, unconfined creative space for voice, gesture and image, a space for asking questions, where the local and virtual converge, a flow toward new literary/performative ecologies, where personal experience and that of a common humanity coalesce, where the national and the global at least overlap.

But we arrive, suddenly, at a Kosmopolis under threat, a Kosmopolis interrupted in a world now contracting with re-imposed borders, travel prohibitions, new limits and restrictions, with human interaction itself in danger, where isolation becomes our new ecology, where the Net takes on added, new dimensions. One title for the dance that Samuel Beckett’s Lucky performs in Waiting for Godot is what Pozzo calls “The Net. He thinks he’s entangled in a net” (27). We all seem currently entangled in, not a, but the Net.

The work of Samuel Beckett is a case in point as the Twitterverse is awash with comments declaring Beckett the poet of isolation, the writer for our COVID-19 pandemic. Beckett himself lived through the Influenza pandemic of 1918-19, which was entangled in and exacerbated by the first of our Great Wars and subsequent mass victory celebrations. The war ushered in our Modern technological age with all its vulnerabilities. In Ireland of 1918-1919, as the Anglo-Irish War, rather the Irish War of Independence, was coming to an end, some 800,000 Irish were infected, some 23,000 lives lost over a 12 month period according to The Enemy Within exhibit at the National Museum of Ireland (q.v.). The Irish census of 1911 had the population at about 4.4 million, diminished to 4.23 by 1923, that during the Irish civil war. There was something of a denial of science amid this “Spanish Flu” of 1918-19, which had a certain kinship, at least in Ireland, with the folk wisdom of the Great Famine (1845-1849), which, according to folklore historian Simon Young, had “quasi-religious” overtones: “There was the belief among some Irish potato growers that it was the fairies’ disfavor that brought down the blight on the land. Fairy battles in the sky – fairy tribes both fought and played hurling matches against each other – were interpreted as marking the onset of the famine: a victorious fairy army would curse the potatoes of the enemy’s territory” (The Irish Times, 2019). Current religious conservatives of all the major religions see the current travails and threats to civilization as the wrath of G-d inflicting plague as punishment for violations unspecified. Think “Job,” a favorite text of Samuel Beckett (and many of us, for that matter).

How much isolation and religious causality the young Beckett was subject to in 1918 as the War of Independence and the war against the invisible invader raged is difficult to assess, but he must have been sequestered, his contacts and friendships limited in the semi-rural Dublin suburb of Foxrock. The body of literature he would finally produce would be marked by an urbanity and sophistication, a cosmopolitanism, say, and yet much of it set in rural isolation, the urbanity of Godot played against the rurality of place. The sequel, Endgame, depicts the life of enforced isolation if not quarantine complete with its quotidian irritations. If nothing else, Clov may have cabin fever. And Happy Days, a paean to confinement and Beckett’s return to a two-act structure, is played against an expanse of nothingness as Winnie laments the loss of “the old style.” In many respects, Beckett’s work plays out the tensions if not contradictions of today’s Kosmopolis.

The current conference and festival of that title allow us to examine both sides of the Kosmopolis through persistent literary and performative experiment, part of a decade-long research project under the auspices of the Between.Pomiędzy conference and The Samuel Beckett Research Group at the University of Gdańsk, research in conjunction with laboratory theatre projects in the experimental tradition of performance as research, the “tradition” in which I still see Beckett, even as he has been too often co-opted by mainstream theaters with actors chosen for their marquee appeal. Charles Marowitz sketches the outlines of that laboratory tradition in terms of his collaborations with Peter Brook in the 1960s, “Peter took many of [Antonin] Artaud’s ideas and gave them a form they never had before; he worked closely with Jerzy Grotowsky [sic] and that minimalist approach to theatre unquestionably influenced his own scaled-down work on the classics.” I would like to think that my work with the Samuel Beckett Research Group and the several productions developed, or at least begun in Sopot, Poland in 2015, 16 and 17 were not intended to be imitative of Brook, or even of Jerzy Grotowski’s Laboratory Theatre, although they were laboratory experiments conceived and executed in Poland so some comparison seems inevitable. They instead continue a line of theatrical research-driven less by entertainment value or even public performance than by textual archaeology, a probing to understand more fully theatre as a mode of discourse and to dig further into particular works written for performance or not, the potential of which, intellectual, aesthetic, psychological, has been under excavated. The issue, then, is not so much how much scholarship, information and background one brings to rehearsals as a director, since, for a scholar, it is difficult to avoid being fully immersed in the critical discourse, but how open one is to possibilities. Central to an effective laboratory research process, then, is the avoidance of standard hierarchies of theatre, and such hierarchies are often embedded in the names of theatre groups, actors’ theatres, directors’ theatres, playwrights’ theatres, since the key to laboratory theatre is not anticipating results but, instead, allowing the process to work, or allowing participants through that process to discover what will work and what will not, and not to stop when one discovers what might work but to dig further for what else might work. Such an approach is different, I think, from directors who want nothing to do with the critical discourse of a work, its critical tradition before they take it on in rehearsals — or ever, for that matter. Such avoidance is simply an argument from ignorance. That said, the critical discourse should not be imposed from on high as something of a preconceived framework.

SE Gontarski at Between.Pomiędzy. Photo by Marsha Gontarski.

Ghosts in the Laboratory, Ohio Impromptu, et al.

Some things we do know before the rehearsal process; there is, after all, a text. In Ohio Impromptu two figures seated at a table are “As alike in appearance as possible,” as the text reminds us. That is, they are not immediately identifiable as the same person, as they are in Charles Sturridge’s misguided “Beckett on Film” version of 2000, in which Jeremy Irons plays both Reader and Listener. But, at the very least, they should appear to be materially equal entities, and two physically present bodies, which is not the case if the same actor plays both parts. And yet the narrative or memoir read by the figure functionally called Reader suggests otherwise, he (presumably) a spiritual representative of an absent one, a former lover. If we assume some continuity, some congruence between the visual image and the narrated images, a self-reflexivity to the performance, say, or an embodiment of the narrative, that is, theatre as illustrative of a text or its duplication, then one of the perceived figures on the stage, and perhaps the one apparently controlling the reading, the one called Listener, is a material presence, the other, an emissary, a shade, a spirit sent by the absent, departed lover for something like consolation, “my shade will comfort you,” may not be. Our perception then may be confused or faulty, the stage image “ill seen,” in Beckett’s oft used phrase, since at least one of the figures may not be there — at least not as a material presence.

Something of a dream may be suggested here as indicated in the narrative by third person pronoun, “in his dreams … ,” but treating the work like a dream play does not necessarily solve the issues of presence and absence, the material and the immaterial, text or language and image. Moreover, the narrative suggests something of the fluidity of being, of parting and reuniting as the Seine divided by the Isle of Swans is reunited on the far side of the Isle, and so finally two or the separated “grew to be as one.” Is this merging, this reunion, that of the river, the lovers of the narrative, or of the two figures we believe we perceive on stage, one apparently material, one not, or the merger of image and language, or language into image, or dream into reality, or, as the narrator of Company says, vice versa? But each of these possibilities is complicated, made problematic, say, as the narrative is both materialized within a territory, the stage space and deterritorialized. We might add that a third active entity is present in the performance, the text itself, at least some forty pages long, on stage, taking on a life, shaping our response to the performance and so to the central, thematic, philosophical issues, but it is, Magritte might remind us, not a text but the image of a text, which, we might say, becomes our third player in the performance, as a link, a bridge, between the lovers, between Reader and Listener, between the real and the unreal, or the real and the virtual, between materiality and imagination, or memory, thus linking past with present, giving spirit or shade a material form and simultaneously questioning materiality itself since both figures may be dream images, or versions of the same figure as “they grew to be as one,” at which union, of course, “nothing is left to tell.” But such a phrase, the “nothing” left “to tell,” is already written, already in the text at or as the telling, pre-existing what we see, the action, the telling, and thus a repetition, a simulation. Text, as text, has presumably been thought and read before, and will doubtless be read again, and again, the imaginative image or memory (and they amount to the same) that we as audience witness has been and will be repeated, with a difference, over and over again, the “Impromptu” not a telos, but a loop, a repetition, always with a difference, and a bridge between the material and the immaterial, between presence and absence, the engagement not between figure and figure but between figure(s) and text, text already written (like a playscript) and so already spoken and now performed, re-presented.

The performance in Sopot took seriously such a multiplicity of images and filled the room with their projections, their visualizations, their materializations, with filmmaker Elvin Flamingo visible to the audience, walking about as he saw fit and projecting various close-ups as he saw fit, offering multiples of images which are beyond words, the audience amid an environment of images, in a room full of ghosts.

The purpose of laboratory performance, then, is as much such discovery as public performance, although the latter is often the driving force of the rehearsals. In a special performance issue of the Journal of Beckett Studies (XXIII.1 [2014]), editors Jonathan Heron and Nicholas Johnson outline their aims in laboratory/workshop exercises and performance, to counter “the distinction, if not the false opposition, [that is, the division] between the archive and the theatre,” which opposition they aim to break down or erase by defining the laboratory as a “liminal space in which discourses and ways of knowing combine. It is [performance] defined by process, uncertainty, and failure, and yet it produces a form of truth” (8), or at least understanding, we might add. That desideratum comes close to characterizing the work we were trying to do in Sopot, their focus on their own production of a Beckett manuscript fragment, the ‘bare room,’ as part of the Samuel Beckett Laboratory in Trinity College Dublin. As Prof. Arka Chattopadhyay suggests in a review of my Ohio Impromptu laboratory production for the Journal of Beckett Studies, “performance in this experimental space of labs and workshops turns into research by expanding the textual and the performative possibilities of encountering Beckett’s pieces in the theatre.” He goes on to note that “Gontarski’s Ohio Impromptu, as we shall see, uses bilingualism and technology to subject Beckett’s play to a dynamic ‘process’ of performance that generates new meanings from the text” (XXVI. 2 [2017]: 291).

In subsequent years through the Theatre Laboratory of the Between.Pomiędzy Festival and the Samuel Beckett Research Group, we produced additional tangible products. The next two experiments continued the theme of ghosts and hauntings into what Derrida has called “hauntology.” These were attempts to dig into the possibilities of the work in intense two-day laboratory rehearsals and performances that relied on a number of creative Polish artists including, for “. . .but the clouds. . .,” filmmakers Szymon Uliasz and Magdalena Gubała and their team, with whom we decided to film and record all of the teleplay except the comings and goings, the patterns of movement. This became especially tricky, as we discovered during rehearsals because those movements require such rapid changes of costume that the physical action, especially performed live, took on an almost comic or at least a mechanical mood, and in terms of Henri Bergson’s critique of comedy (which Beckett read closely) mechanical action itself is a comedic source. Such rapid changes required a dresser (Magdalena Gubała) whom it would be difficult to conceal in live performance and who herself would need considerable dexterity. Such issues are not immediately apparent from a viewing of Beckett’s television production nor from reading the play, and in live performance, they threaten the haunting mood of the teleplay. We went on then to film the entire piece with Polish subtitles.

Subsequently, I created an anthology piece with the same film crew, Beckett on the Baltic to continue the exploration of the haunting effects of lost or abandoned love in Beckett’s poetry and his Krapp’s Last Tape, the film, finally, something of a “Ghosts on the Beach.” Each of these laboratory explorations allowed our team (and the effort was decidedly collaborative) to dig further into the recesses of Beckett’s texts to uncover or to disclose their performative possibilities and implication and, further, to present the results in a Kosmopolis Rebound, suggesting both a hampered or interrupted Kosmopolis in these times of pandemic and its inevitable return.

Works Cited

The Enemy Within, https://www.ouririshheritage.org/content/category/archive/topics/the-enemy-within

Review of Irish Gothic Fairy Stories: From the 32 Counties of Ireland

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by S.E. Gontarski.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.