This article is part of the Dramaturgs’ Network’s Invisible Diaries series.

In a moment of freedom from time and gravity.

Noticing information entering my body

As if there is nothing else in my ear, a blackbird’s song

As if there is nothing else in my breath, sweet scent of lily-of-the-valley

As if there is nothing else on my skin, warm weight of child’s shoulder, cool whisker of May breeze.

Eyes closed.

Caspar the cat. Photo: courtesy of Miranda Laurence

The weather has been beautiful here and I’ve been enjoying the major privilege of a large and leafy back garden – and cherry on top, a hammock swaying in the breeze. During odd moments between parenting, work, and household duties, I’ve found this a most relaxing and refreshing place to be; letting go of the brain, a little, and focusing on the senses, my body’s experience of being in this space.

Over the last year, I’ve developed a series of “Dance Audience Club” sessions: I wanted to gather audience members both before and after dance shows, to talk together. For me, something quite crucial in this was to introduce new ways of thinking for audience members about what it is to watch dance.

One of the starting points I offer is to think more closely about the processes of observation and turn this onto our own bodies. Notice what you’re noticing happen around you. What is it you see, hear? What do you focus on and what do you ignore, or forget? How does the surface of your skin react to the unfolding performance? When does that happen? Notice it. Record it in your mind.

This, all this, can happen before thinking a single thought about “meaning,” “story,” or even “quality.” Simply sitting there and letting it wash over you is not so simple, for it’s also noticing what your particular, unique experience of that washing-over is. Noticing and recording these experiences can be a useful starting point for articulating your response to a watched performance, to yourself or, indeed, to anyone else.

I’ve spent a lot of time facilitating works in progress, sharings, and scratch nights, and through this, I’ve learned a lot about dramaturgical processes. As an attender to such events (and despite the prevalence in dance of the excellent Liz Lerman Critical Response Technique1, I would often notice how many of the feedback sessions would fall back on a process in which audience members are being asked for their opinion about what they’ve just seen, and the artist is defending their work against criticism – or even suggestions for improvement – disguised as questions. This framework can reinforce the sense for an artist that they have to do what their audience expects, and for an audience member that there is a right way of making sense of a piece of dance, and a wrong way.

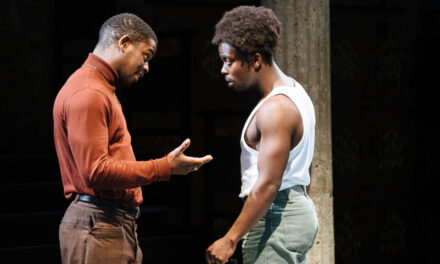

In rehearsal. Photo: courtesy of Miranda Laurence.

When I am facilitating these types of discussions, I’ve tried to introduce three core principles: questions go from artist to audience; these questions are carefully chosen to contribute to the artist’s inquiry at that moment of development; they are carefully worded to best enable all audience members to give an answer, however experienced or inexperienced they are as spectators of dance. These questions tend to ask for “factual” information from audience members: “What images arose for you while you were watching the piece?,” “Were there any moments where you lost attention?,” “What would you say about the piece to a friend tomorrow?.” This can help focus the discussion and make it accessible, interesting and useful for audience and artist.

When I work as a dramaturg in a rehearsal process, one of my main functions is to watch and respond. I don’t always manage to stick to my own principles, and I do find myself getting wrapped up in words and trying to grasp and articulate meanings, often without much certainty. When I’m stuck, it’s always worth trying to slow down, to think about what information is entering my body. What I notice. What is long and what is short. Which sensory organ is particularly tickled.

The difference when I do this in rehearsal (rather than relaxing in a hammock in my back garden) is that I try and notice when these things happen in and to my body, in relation to the work in front of me. What change, or lack of change, causes my breathing to slow? What is it about the movement which focuses my attention; is it in pace, pitch, dynamic? Is there a sound moment that has caused sensations on the surface of my skin?

More often than not, attending to my body can give me enough information to continue the dialogue.

Miranda Laurence is an independent dance dramaturg based in the UK, with over 10 years’ experience working in the dance and arts development sectors. She collaborates with dance artists across the UK and internationally, recently working with Johanna Nuutinen (FI) and Attila Andrasi (HU/ES). Her practice and professional development have been supported by awards from Arts Council England, Oxford Dance Forum and South East Dance.

Her collaborators work in a range of dance forms, from Kathak to screen dance. She is also in demand as a workshop leader, recently invited to Arhus by the Association of Danish Dramaturgs, and by London Studio Centre for their MA in Dance Producing.

Miranda has also directed the Dance & Academia project based in Oxford since 2008, convening a number of seminars and conferences engaging movement practitioners and academics in many different disciplines.

Alongside her freelance practice, Miranda is employed as Arts Development Officer at the University of Reading, where she is developing a strategic arts program for the University including leading on new public art commissions.

This entry appeared on the Blog of the Dramaturgs’ Network on 9 May 2020, as part of the Invisible Diaries series and has been reposted here with permission.

#InvisibleDiaries

NOTES:

- Very briefly summarised, this process invites us to start with the response of the spectator as meaningful for them personally, moving through a series of steps to, finally, spectators giving an opinion.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Miranda Laurence.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.