It’s trite to write about how hard it is to live from lockdown to lockdown; from one mask change to another; from vaccination to revaccination. Yet life consists of platitudes. It is trite to write about the important role that theatre plays—even when talking of online theater—in overcoming psychological barriers, in motivation, and indeed inspiration. The theatre is a breath of fresh air that you breathe in freely, without fear, masks or unpleasant consequences. And air is life. The theatre, in my opinion, really needs a word. Silent theatre too. And these words are always in The Theatre Times. Wise, correct, timely, relevant, honest, and artistic words. Words that are not inferior to performances. The mission of The Theatre Times and its founders is fully manifested in the current era of theatrical calm. Premieres, viewers, discussions – there could have been more, but Melpomene is forced to submit to Hygeia.

In the most critical moments of the pandemic, The Theatre Times continued exploring theatre issues and helping its authors, encouraging them even. The staff of this magazine are not only professionals, but also sensitive, responsive, caring people. Forgive these notes of praise and anniversary speeches, for these are not artistic fiction, but a fact, one to which I am a witness. The Theatre Times celebrates its fifth anniversary. The fifth anniversary. A beautiful tender age. It’s not much, but if you think about the achievements—from festivals to multimedia projects—you realize that The Theatre Times has more than twenty-four hours in its day. The theatre has its own laws, which are not always subject to the laws of nature and reason.

From a Russian perspective, The Theatre Times is a window into the theatrical world—a kaleidoscope of everything bright, interesting, and relevant. This is a platform not only for reviews and interviews, but also for theatrical materials, as well as acutely topical articles in which authors can express their opinions without censorship. The Theatre Times is a team of editors and proofreaders who love their work, respect authors, and help them to improve. At The Theatre Times, you want to be better and grow above yourself. A feeling far stronger than borders, distances, restrictions, and time zones.

Happy birthday, The Theatre Times, may your future be filled with bright performances and good news.

In Moscow, autumn heralds new covid restrictions. Autumn rhymes well with the Autumn Sonata, which I would like to tell you about today. This is not the premiere, but one of the most successful performances of the Sovremennik Theater directed by Ekaterina Polovtseva. This is a quiet yet firmly resonating performance.

The cult film of the same name by Ingmar Bergman is hard to forget. The author and director transgresses the threshold of pain, telling the story of the relationship between mother and daughter who make the fateful step from love to hate. Monologues of Ingrid Bergman and Liv Ullman, full of mutual reproaches and insults, do not seem to break the posthumous silence of the night conversation. With all emotions burned out during the seven years that separated the heroines from each other, all arguments in defense are rejected and a guilty verdict is passed. The simplicity and composure with which the story is palpably unnerving.

The Autumn Sonata in the theatre is constantly interrupted by the audience’s laughter and even laughter from the boards. The hall is adequate, the artists even more so. The story remains the same as does the author, but it would almost serve as an injustice to label this performance as an adaptation. The text here is actually somewhat expanded compared to the film. Bergman’s script, when transferred to the stage, suffered trauma—the genre is replaced with tragicomedy, sometimes melodrama, but the drama itself is absent.

Nordic restraint and severity are melted, the ice edge of old grievances is broken away and a fascinating family scandal is presented—with wine, women’s screams, tears, and ultimately revelations.

Charlotte – Marina Neyolova. Autumn Sonata, Moscow Sovremennik Theatre. Photo by Elena Sidyakina.

In the role of a famous pianist making world tours, Marina Neelova resembles Chekhov’s Arkadina. She plays out her life as though a pianist. Dynamic, fussy, playful yet in the Maestoso fashion. The best anti-techniques of the actress are more than appropriate here. The heroine manages the role of a visiting celebrity better than the role of a mother, and Charlotte has something to reproach. But not Charlotte-Neelova. The endless stream of accusations of the daughter overrides the main argument of the mother.

A sensual, captivating scene and an argument that is difficult to refute. Daughter—played by Alyona Babenko—loses the game of “daughter-mother”. Her heroine did not get used to the role of a daughter; fate did not entrust her with motherhood (abortion and the death of a young son). The name Eve (“giver of life”) turns out to be a mockery.

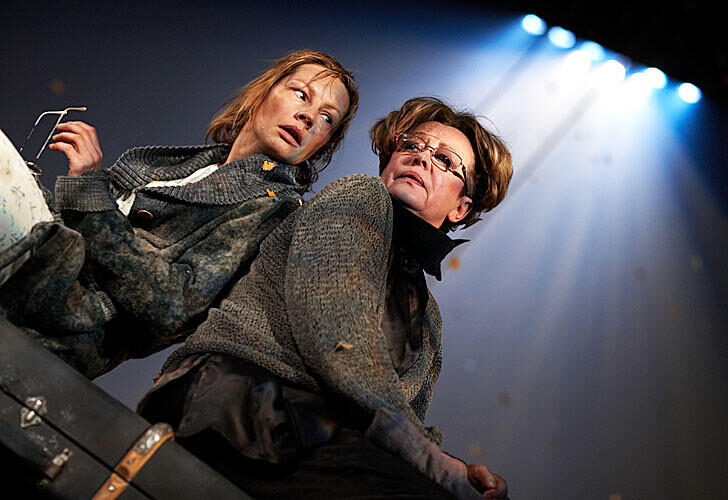

Charlotte – Marina Neyelova, Eva – Alena Babenko. Autumn Sonata, Moscow Sovremennik Theatre. Photo by Sergei Petrov.

The heroine is more comfortable in an internal monologue and in a dialogue with her deceased son, i.e. with those who will not object, will not tease, will not overshadow. Mediocre, she seeks solace in religion, marries a pastor, but is still unable to comprehend Christian forgiveness. For the sake of self-pity, she selfishly takes the afterlife from religion (there is no need to torment the soul with thoughts about the death of her son), from science—the teachings of Freud, who gave mankind the privilege of blaming ancestors for the failures of descendants.

Perception depends on the viewer. A lopsided stage, graying beams, dead leaves, gaiters, and a lonely boat at the pier go about in portraying Eve’s autumn. A red dress, rosy apples under a golden carpet of leaves, and a swing—this is the Indian summer of her mother Charlotte. As the name implies, there is a lot of music in the Autumn Sonata. All the musical moments that are talked about on stage are heard from the stage. The program of the performance is similar to the program of the concert: Bach, Beethoven, Schoenberg, Bruckner, Bartok, and of course, Chopin, who became the spark for the Bickford chord smoldering away for seven solid years.

There is also music in her words. Remembering the day of her husband’s death, she recalls the annoying sounds of construction outside the hospital window better than the farewell itself; only the deafening memory of pain remains from childbirth. The family chronicle is restored by tours and concerts. Charlotte is tormented by the unusual silence of a boring house, as if sensing that its silence will be broken. Yet even this painful visit might be justified by a potential interpretation of Bartok that is easily conjured by the mind.

There is also something Chekhov-like in this Russified history. The daughter, crying, talks about how, sitting next to her father, she reread her mother’s letters—much like in “Uncle Vanya”. Her reproaches refer to Voynitsky’s excited monologues, what’s more, she reaches the point that she could become a great pianist; hence Charlotte’s thoughts to go to Africa (like Astrov); here even “smell like sulfur!” as in “The Seagull”. It occurs to Eve to commit suicide at the hour when her mother is rolling away from this “sleepy hollow”, but this thought looms and can be absorbed by hope.

Lost and missed children, blood relatives who are related only to myopia, fear of touching because “grief is contagious”—these phantoms inhabit the performance. Its finale, however, is cleansing. Reconciling rather than humbling. The house will stand, because its family hearth remains firmly intact.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Emiliia Dementsova.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.