Day four of the Between.Pomiedzy festival featured Virtual Beckett, the third seminar by the Beckett Research Group of Gdańsk. This session opened with a presentation by the artistic directors AnomalousCo (and authors of this article), Kathryn Mederos Syssoyeva (Boston, US) and Diana Zhdanova (Moscow, Russia), and our collaborators, on our recent Laboratory/Festival, Beckett & the Virtual. This was followed by a talk by Nicholas Johnson, Associate Professor of Drama at Trinity College Dublin, co-founder of the Trinity Centre for Beckett Studies, and co-author of Experimental Beckett (Cambridge UP, 2020), with closing remarks by Beckett scholar and director S.E. Gontarski. These presentations followed a special session, Godot in Wuhan: a conversation with Professor Peng Tao of the Central Academy of Drama, Beijing; Tomasz Wiśniewski, founding director of Between.Pomiedzy, and director Wang Chong of Théâtre du Rêve Expérimental, Beijing, whose virtual Waiting for Godot at the start of China’s pandemic lockdown was streamed by over 300,000 viewers.

AnomalousCo

We began the discussion with an overview of Beckett & the Virtual, a laboratory and festival cooperatively created by 35 theatre directors, actors, designers, visual artists, composers, and theorists, collaborating virtually from the US, Chile, France, Poland, Estonia, and Russia. Taking the short plays of Samuel Beckett as the subject of our experimentation, our aim was to investigate virtual space as a distinctive language of performance, at the crossroads between theatre and film. Much of Beckett’s experimental work is situated at the intersection of the technological and the psychological, exploring a consciousness split via mediation into self and other. Like so many theater makers in this time of social distance and technological connectivity, we found in Beckett a playwright for our moment.

The laboratory portion of the project commenced with two days of discussions, presentations, workshops, and breakout groups on technologies of online performance, acting methods for virtual space, small-screen aesthetics, audience-performer interaction, and the question of holding true to Beckett’s directives in a new medium. Over the course of four intensive weeks, our temporary collective produced 14 experimental works, variously performed in English, French, Russian, and Polish. Teams worked autonomously to develop their productions, with the group re-convening on weekends to discuss emerging work. The laboratory culminated in a 7-day Virtual Festival, streamed globally.

Continuing the presentation, we introduced the theme of Beckett’s constraints and the challenge of finding freedom within these texts. At the outset, we had declared that “we are staging Beckett to stage Beckett.” In practice, faced with the provocative freedom of virtual space, our relationships to the texts proved complex. Some productions indeed stayed faithful to Beckett’s directions, such as Krapp’s Last Tape with Lloyd Bricken (Alabama, US), directed by Marc Grandsard (Nantes, France). Shot in a realistic, minimalistic space (a basement), Grandsard’s single take of Bricken’s performance blurred the lines between theater and film, leaving audiences with the impression of witnessing live performance. Rockaby, too, hewed close to Beckett, and similarly blurred the line between theatre and film. Directed by Zhdanova and performed by Syssoyeva, Rockaby was transmitted live via Zoom from a tiny room transformed with black curtains into seemingly theatrical space, and fitted with multiple mirrors to refract the rocking body across four planes.

Other productions in Beckett & the Virtual straddled fidelity and inventive liberties. Ohio Impromptu, directed by Kyle Gillette (Austin, US) and performed by Gillette and Bricken in a single, Zoom-pre-recorded take, held faithful to Beckett’s blocking, but departed vocally:

Beckett’s text immediately affected me for its rivulets of rhythms and its lyricism. I initially picked up a one-stringed instrument, an ektara, to rest around a single tone while I let the melody and texture come forth, become full – the impulses of actions embedded in Beckett’s rhythms. As that clarity increased, so did my ability to console, shake-up, haunt, upbraid, inspire, elegize – as the Reader for my Listener. It all became a ritual for Kyle and me, a poetic liturgy… not represented but done. (Bricken)

Zhdanova’s Rough for Radio I (streamed on Buzzsprout), with Syssoyeva and Marc Grandsard, likewise held true to Beckett’s structures, while departing vocally:

We decided to keep radio plays as radio plays – no images. But what is Radio in 2021? We created a jazz-funk-rap composition, to avoid the clichés of Beckett performance and hook the speedy attention of a contemporary listener, while retaining the layered meanings of Beckett’s dialogue. (Zhdanova)

Daniel Jackson’s Ghost Trio (streamed via Twitch) also adhered to Beckett’s blocking, but departed in form, taking Beckett’s übermarionette to its logical extreme:

Built in the Unity Game Engine, software primarily used to create video games, its primary character, F, was played by the 3D model for Dobie, an anthropomorphic wolf from the Animal Crossing video game series, and the Female Voice performed by the MacOS’s built-in text-to-speech engine. F/Dobie was rigged to be controlled from above, like a marionette, his physical performance dictated by external forces in concert with a simulated physical environment; each time Ghost Trio is shown, the compiled code that comprises the piece is executed, producing what is essentially live performance without human performers. (Jackson)

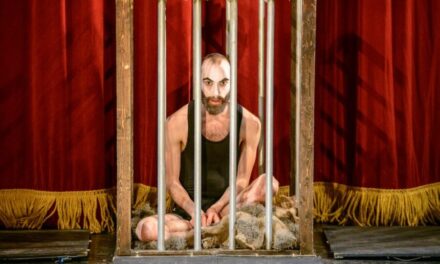

Still other productions in Beckett & the Virtual operated on what Wiśniewski called “our memory of past performances, of Beckett’s words, of remembering the text itself.” Galya Zhdanova’s (Tallinn, Estonia) Come and Go (with G. Zhdanova, Nadya Chernykh, Asya Shirshina) was live-streamed from multiple locations – a rehearsal room, domestic spaces (tub, basement, stairwell), and the street, interspersing Beckett’s text with personal monologues drawn from rehearsal études. Philip Salata’s (San Diego, US) Rough for Theatre I – which incorporated found footage from surveillance cameras and Google Earth – retained fragments of Beckett’s lines, performed in Russian and Polish by Alexandr Drugov (Saint-Petersburg, Russia) and Piotr Siwek (Warsaw, Poland), with the full English-language text running across the bottom of the screen.

Rough for Theatre I with Alexandr Drugov and Piotr Siwek. Directed by Philip Salata.

The point of departure was to use all tools available to us to transform the obstruction of our physical distance into a kind of game, through which we would discover the worlds of these characters. It became immediately apparent how many cameras surround us, and how shockingly accessible this technology of surveillance is. Not only have personal tools of self-surveillance become second-nature to us, but the planet is littered with millions of cameras constantly streaming. So the actors became like journalists, recording their own lives while reacting to the script. As a director my game was to find all possible portholes to their physical realities – an elaborate game of voyeur with a mediated public peephole to places all over the globe that are already layered with history and potential dramaturgy. And so, for instance, when I coordinated with Piotr to take the tram to the Plac Zbawiciela late at night, to film him through a city webcam dancing on an immaculately lit urban stage, I could not help but recall Julita Wójcik’s flower rainbow sculpture, burned to the ground three times in that very place. (Salata)

Considering this contrast of styles and methods, Diana Zhdanova remarked on the freedom of our laboratory process: a networked approach to collective creation emphasizing autonomy within group work and holding space for border crossing and multiplicity: multiple countries, languages, platforms, approaches; cross-border collaborations between artists who have never met in three dimensions; actors directing, directors acting, performers of necessity designing and filming their own work. Syssoyeva remarked on the borderlessness between the professional and the personal in our process: “What does it mean to bring the theatre home?” Zhdanova noted, too, that “Zoom space is not a holy space like theatre” – it is a commonplace environment and, as such, artistically challenging.

Kyle Gillette proposed that virtual space may be understood as a form of “poor theatre”. “This can be taken ironically, in a Grotowskian sense, because there are all these technologies involved – at the same time, the form is impoverished in its restrictions.” And impoverished technology, he pointed out, is embedded in so many of Beckett’s works. “As early as Krapp’s Last Tape you have all these technologies of remembering that are incomplete. It’s interesting to consider the glitches, the fragmentation of Zoom in this context,” as well as “the sense that the virtual is something that at once connects and isolates. One becomes another to oneself.”

Przemek Wasilkowski, who directed Adrianna Cudnik in Beckett’s That Time, spoke of virtual performance making against the backdrop of “the whole history of theatre in darkness.” For Wasilkowski, the entire project was an attempt “to understand what can be if we are out of this darkness.”

Nicholas Johnson

The talks by Nicholas Johnson and S.E. Gontarski, which followed the presentation on Beckette and the Virtual, focused on media and experimentation. Johnson began by remarking on his “tremendous joy” at witnessing a continuity of experimentation with Beckett’s work – “the living afterlife of a writer who reaches into us as people.” For Johnson, virtual representation is as critical to the survival of Beckett’s legacy as is embodied performance. “Beckett survives because we are people who have heard the words or seen a play – or seen the images – and thought about it.”

Addressing the presence of media in Beckett, he continued, “We cannot easily disentangle the technological or the mediated from the human. But what Diana’s comment about the life that we are living on zoom reveals, and I think the whole pandemic here has revealed, is that we are in fact engaging in yet another technology of being that is embedded in our lives, in our culture, in our emotions.” And Beckett “always has been a go-to writer at times like this.”

He went on to discuss Beckett’s estate and representative agents, and the murkiness of “rules” – such as gender-traditional casting, and strict adherence to settings – by which directors of Beckett’s work have been, historically, bound. These, he believes, are in reality both fluid (depending upon the scale and profitability of productions) and in flux. Certain social phenomena, he argued – from our dynamic, contemporary understanding of gender to the un-monetizable proliferation of Beckett performances, memes, images, and quotes across the internet – are unstoppable. Sooner or later the estate must inevitably relinquish some measure of control.

As for technology, he argued that it is a disservice to Beckett to hold rigidly to the details Beckett envisioned in the moment of writing. Taking Krapp’s Last Tape as an example, he pointed to the first stage direction: “‘Late evening in the future’” – a future “envisioned in 1957.” To stage Krapp with tape recorder immediately raises the question, why does this future resemble our past? “Truthful experimentation looks futuristic now. We need to see the work as a living thing that has to progress and adapt in order to survive.” With TCD’s Samuel Beckett Laboratory, which Johnson directs, he experimented for three years with Beckett’s Play – “particularly interesting, because Beckett experimentally adapted this play himself, for different media – radio, film”. He transformed the show for VR, a medium which, while futuristic now, is nonetheless taking root in our culture.

“Bringing Beckett’s plays into a digital culture is already adaptation, whatever we think,” he concluded. “Different spaces and rules. I encourage everybody to experiment. Thanks to that Beckett will still live.”

Nacht und Traüme with Adrianna Cudnik (pictured), Alina Pokrovskaya, and Diana Zhdanova. Directed by Kathryn Mederos Syssoyeva.

S.E. Gontarski

SE Gontarski closed by addressing the role of technological innovation – past and present – in Beckett’s work. For Beckett, one of the first major, technological shifts was the proliferation of recorded music, whether conveyed by radio or by phonograph. Suddenly, in Beckett’s lifetime, “one does not have to go to the concert hall to hear this music.” Music enters the home – and in the process, “communitizing” breaks down. A loneliness and isolation emerges – such as we find, say, in Nacht und Träume – akin to the loneliness and isolation of audiences viewing performance via zoom. “So I’m thrilled with this project and the thread which runs through this work, which is that we shouldn’t be applying old standards to our contemporary cultural situation.”

“Theatre is multiple,” Gontarski concluded, “It has innumerable manifestations. And in this current moment, not only is the wave of Beckett’s work unstoppable, but also the media transformation is unstoppable and that’s where we are today.”

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kathryn Mederos Syssoyeva and Diana Zhdanova.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.