Solomon Mikhoels, the beloved star of the Soviet Yiddish theater, was once asked how long he worked on the role of King Lear. Mikhoels’s reply was: 45 years. Mikhoels explained that he played Lear in 1935 when he was 45, so he worked on the role all his life, that is, 45 years. “This means that all of my life, experience, impressions, knowledge, and all the power and discipline of my intellect were invested in that role,” wrote Mikhoels. Playing the role and performing on stage was not merely acting for Mikhoels, but what he called “exposing [his actual] perceptions of the world and [of his] weltanschauung” at a particular moment of his life. Mikhoels used to say that the calendar of the roles he played was essentially the calendar of his life. Unfortunately, a calendar is not an archive: the roles cannot be preserved there. They are as ephemeral as time itself. They can be preserved in the memory of the generation that witnessed them, and then as a myth for one or two generations to come, and then, likely, forgotten. However, manuscripts don’t burn, so roles and entire theatrical movements could thus be archived and preserved.

According to his contemporaries and himself, Mikhoels “hate[d] writing and keeping any records” and preferred “the live word of mouth.” However, reluctantly, he entrusted some of his thoughts and creative ideas to paper. Hence, fortunately, his voice survives, preserved in Mikhoels’s published and unpublished articles, essays, and speeches on various aspects of theatrical art and acting. From these archives, his roles can be recreated and his life—dramatized. Thus, a few years ago, I started working on a biography of Mikhoels by writing his imaginary autobiography, a text he neither wrote nor even conceived of himself. Eventually, my text evolved into a script, the life drama of Mikhoels.

Aleksei Granovskii (Wikipedia).

Mikhoels is both playwright and actor in this drama. As an actor, he was taught by the founder of Soviet Yiddish theater, Aleksei Granovskii, who, in turn, was a student of Max Reinhardt, the founding father of German theatrical expressionism. Following Reinhardt, Granovskii sought to build a Yiddish art theater, creating a new life on the stage, rather than re-creating real life by theatrical means. In such a theater, actors were supposed to expose rather than impersonate dramatic characters. As Reinhardt put it, an actor should be both a “sculptor” and “sculpture,” having equal footing in imaginary and real worlds, while equally alienated from both of them. While, according to Stanislavsky’s system, acting was to be propelled by stage movement and mise-en-scène, for Granovskii, the acting was propelled by the actor’s reflection that framed the movement and mise-en-scène. Thus, in the spirit of Granovskii, I tried to play out Mikhoels’s reflections on theater and life as an experimental “autobiography” of Mikhoels, in collaboration with actors Mikhail Nosovsky (Nos Theatre, Toronto) and Roman Freud (Steps Theatre and The Russian Arts Theater, New York).

Mikhoels’s art and life were affected by another aspect of German theatrical expressionism—political or epic theater, best represented by director Erwin Piscator and playwright Berthold Brecht. In Piscator’s expression, “art was expelled from the stage” to be replaced with “statements” used as means of “performing politics.” Mikhoels shared this vision. In his article “About Expressionism,” published in 1934, the same year Piscator’s 1929 programmatic book Political Theatre was translated into Russian and published in the USSR, Mikhoels envisioned performance as politics and the actor as a political leader.

He wrote, “When the actor [engages and controls the audience] … then he feels that he is a leader. And what does it mean to be a leader? It means to be in charge, to lead. And it’s precisely this that the actor seeks to accomplish.”

Mikhoels used the stage as his principal means of addressing the Jewish public and saw the theater as the principal place where he could meet Jews and lead them. His choice of the acting profession, which he made in mid-life, was by no means coincidental. Rather, it was based on Mikhoels’s singular vision of “acting,” anticipating the 21st century’s “performance society,” back in the 20th century—the age of mass politics, world wars, and social revolutions. In Mikhoels’s view, the actor is essentially a leader who leads the audience inside the theater and beyond it. Mikhoels never joined the Bolshevik or any other party, lest his creativity be affected by party politics and external ideology. However, his art was political, based on a political platform of his own—a Jewish, ultimately Biblical vision of life and a Jewish attitude toward the ever-changing world. In his words, Mikhoels “lived fully in unison with the life of the people … [and was able to] analyze and understand their reality.”

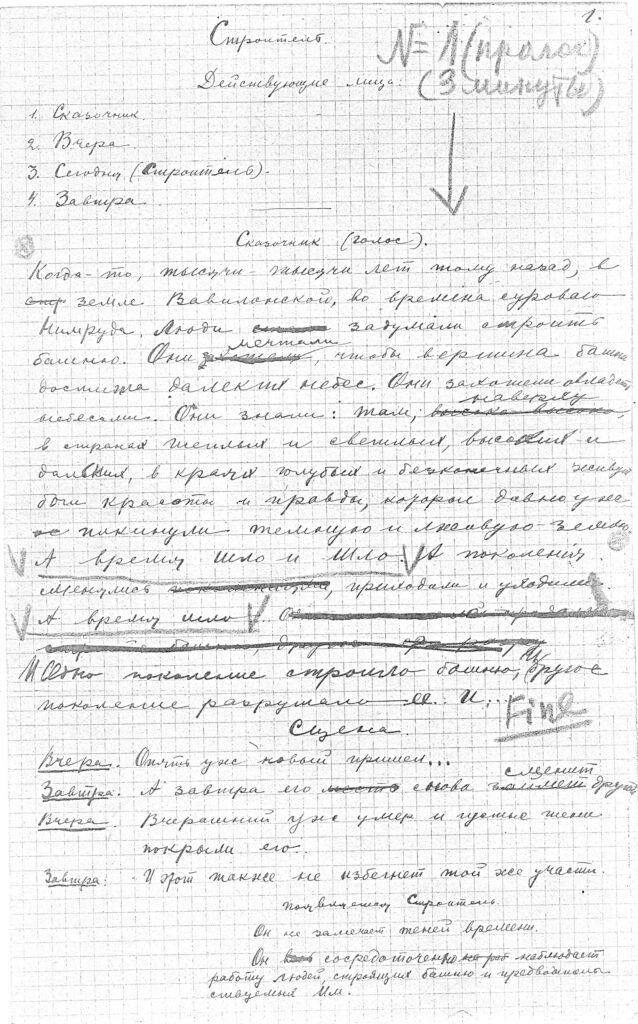

Manuscript of Builder by Solomon Mikhoels (A.A. Bakhrushin State Theatrical Museum in Moscow. F. 584. D. 51. L. 1).

In the spirit of Piscator’s political theater, Mikhoels not only performed politics but also wrote his only play, Stroitel (Builder, 1919), as a manifesto of a new theater with political import. The avant-garde Builder directly addresses one of Henrik Ibsen’s last plays, the symbolist Master Builder (1893). The founders of avant-garde Yiddish theater, Granovskii, and Mikhoels, brought the symbol of Henrik Ibsen to the. stage in order to publicly rebut his ideas and proclaim their own path in art. In the finale of the Ibsen play, the architect and builder Halvalrd Solness climbs the scaffolds of a newly built tower to reach the skies and listen to the eternal harp music of the high spheres; suddenly, he falls down and dies. Mikhoels’s “Builder” is both a sequel and a prequel to Ibsen’s Master Builder. One may argue that Builder begins immediately after Solness’s fatal fall, but Mikhoels set it “thousands and thousands” of years ago in the land of Babylon, where, as written in the preamble of the play, “People began to build a tower touching the heavens. People desired to reach the heavens where the gods of beauty and truth are hiding after they left duplicitous earth.” The curtain opens. The new Builder is onstage watching the construction. He is full of energy and joy, listening to his brother-builders singing while they work at the top of the tower. A couple of strangers are watching him: Yesterday, a crooked figure in black, and Tomorrow, a blurred figure in shining blue. Yesterday says that there is nothing new under the sun—new builders come and go every day, but the tower has never grown beyond certain limits. Eventually, the day comes to an end and at dusk, the builders start to fall from the top of the tower, totally exhausted. The exhausted Builder lies on the earth, dying. While Yesterday laughs, Tomorrow tries to encourage the desperate Builder.

“Your brothers are dead, and you will follow them soon. But new builders are coming … They won’t build walls with bricks and clay—they will build with the power of their vision … The tower must not be built the way peoples’ dwelling are built; the new builders won’t build it with stones. It’s not stone, but our spirit that will bring the light and dispel the darkness that hides heaven.”

The Builder dies. The song of the emerging new builders grows stronger from offstage.

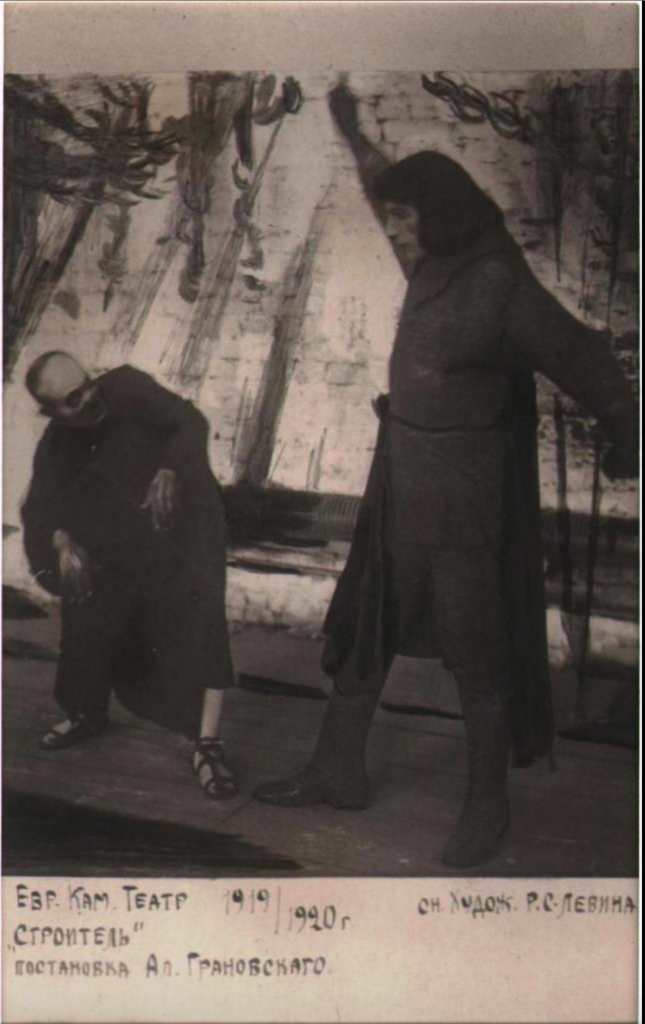

Solomon Mikhoels as Yesterday, Aleksei Granovskii as Builder. Yiddish Theatrical Studio, Petrograd, 1919-1920 (Matvei Geizer, Mikhoels. Zhizn’ i smert’. Moscow: Glasnost’, 1998).

Using the form of symbolist drama, Mikhoels and Granovskii advanced their anti-symbolist agenda. The avant-garde Yiddish theater re-enacted on its stage the death of Ibsen’s Solness, shown as a symbol of the death of Ibsen’s individualism. It is not a coincidence that in the finale of the Builder, the exhausted and dying single builder of the present is being replaced by the many coming builders of the future. While the single builder of the present is destined only to continue building, it is the collective of future builders that will successfully bring this work to completion. The manifesto of the Yiddish Studio, distributed at the first performances, reiterated that “Jewish writers, artists, musicians, actors should not just stand by watching … but proudly raise the tower [of the new theater]. Let the language of its builders be understood by all, let the top of the tower reach the bright Sun of beauty.”

Builder, show poster. Hermitage Theatre, Moscow, November 25, 2019 (design by Mariia Iakubovich).

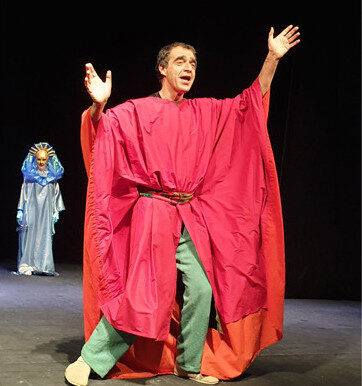

Mariia Iakubovich as Tomorrow, Aleksandr Rezalin as the Builder, and Igor Pekhovich as Yesterday. Act I: Tower of Babel. Hermitage Theatre, Moscow, November 25, 2019 (photo by Granovskii Theatre).

Builder premiered in the summer of 1919 in Petrograd, and was performed by the Yiddish studio a few more times, including summer tour performances in 1920 in Vitebsk. In Vitebsk, Granovskii and Mikhoels met Marc Chagall, whose creative vision helped Granovskii transform Reinhardt’s legacy into his own original type of theater, and even helped him to create “the Granovskii system” of acting and stage direction. Many decades later, Russian actor and director Igor Pekhovich, who defined the Granovskii system as a creative synthesis of Reinhardt’s theater, Chagall’s art, and Mikhoels’s “Biblical imagination,” tried to recreate and develop this system, founding Moscow’s “Granovskii Theater” in 2013.

On November 25, 2019, one hundred years after the 1919 Petrograd premiere of Builder, thanks to my discovery of the never published and long considered lost manuscript of the play in a Moscow archive, and to Igor Pekhovich and his Granovskii Theater, Mikhoels’s play returned to the stage at Moscow’s Hermitage Theater. Pekhovich directed the play and co-starred as Yesterday, with Mariia Iakubovich (Tomorrow), Aleksandr Rezalin (the Builder), and Oleg Sankovskii (Chinese Warrior and Prison Guard). Pekhovich added an epilogue to Mikhoels’s original one-act play: two shorter pantomime acts tackling other massive historical building projects—the Great Chinese Wall and the atomic bomb. According to Pekhovich, “It was impossible to fully restore the original 1919 production. However, placing it in a historical perspective and universal context helps to grasp its original message.” This message is essentially political: the vicious means of building a “brighter future,” such as blind faith, forced labor, mass destruction of life, will bring a vicious future.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vassili Schedrin.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.