Last spring, dementia made it to Broadway! Let me be clear: I am an Avant-garde type and I am wary of Broadway. The intersection of Theater and Age is a subject of interest to me, but so far as I know, until last season, it was not of interest to Broadway. But suddenly, dementia–and not just any old dementia but the dementia of the old–emerged in this very American funhouse–that is, Broadway. What does this mean?

The Father, by the 38-year-old French playwright Florian Zeller, came to Broadway fresh from its enormous London West End success (fresh in turn, from its enormous Paris success) in a translation from the French by the redoubtable Christopher Hampton. Zeller’s The Father, incidentally, is not to be confused with the other Father, THE Father, the world-famous 1887 play by August Strindberg, which by a strange imp of fate was revived, as they say, at the very same moment this past spring by the Theater for a New Audience in Brooklyn. Strindberg’s misogynist fate-drama was sensational in its time for its attack on the father’s wife. She drives the father mad because she thinks he’s gone mad, and in the course of the play, she succeeds: he gets carried off at the end in a strait-jacket. But this father, André, an impressive bourgeois living in Paris, is really losing his mind to probable Alzheimer’s; its twelve scenes anatomize his inexorable decline, from mislaying his watch to his incarceration in a nursing home, unable to remember his own name.

Are you still with me?

Two dramaturgical mechanisms, like little pacemakers, are embedded in the play. The first is what I described in my previous blog as the Dementia Plot—this time in its purest French form: the Father’s daughter must choose between caring for her father or moving with her fiancé to London. (Since the 17th century, French plays have been motored by conflicts between absolutes–love and duty, passion and marriage, etc.—that’s French dramaturgy: can’t be helped).

The second pacemaker is also French, but of more recent origin. Instead of just telling a sequential story, the play’s scenes are written from the perspective of a figure who is mentally unreliable. So, does the father have one daughter or two, is this his apartment or his daughter’s? Is Pierre the daughter’s husband of many years or her fiancé? The play moves along two tracks at once, one of normative chronology, the other of subjective fantasy. Although this second device has been interpreted by reviewers as the father’s mind-according-to-Alzheimer’s, it is just as much the trickle-down result of French Surrealism and its younger cousin, the Absurd.

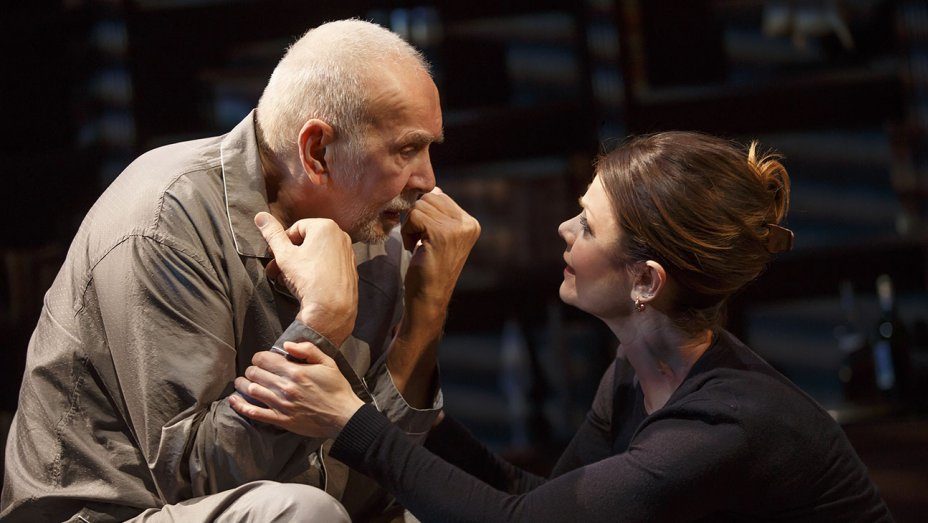

However, as the play’s French, British, and now American producers knew and know, it is casting that really drives the interest and success of this play. The central role of André, the father, requires an impressive older male actor, a Lion-in-Winter type. The father’s decline, from a man of authority who has mislaid his watch, to the pathetic, sobbing child of the final nursing home scene, is meant to be seen as a great fall from a high place. Great stars played the role in Paris and London. They won awards and had long runs. In New York, the then 78-year-old Frank Langella won a Tony for Best Actor in the role. But the show closed after a little more than nine weeks plus previews. Short run. What happened?

Maybe Broadway audiences couldn’t be persuaded to spend a hundred bucks on dementia. Maybe its producer, the Manhattan Theatre Club, a long-established off-Broadway institutional theatre, misjudged the New York appetite for a European hit play about the catastrophe of aging, and should have reserved this play for its smaller space rather than its newly-acquired Broadway house? But the play is shallow. And Langella, with his pale, wounded eyes, like an older Montgomery Clift, is not the actor to mask its flaws with a macho authority. Langella’s performance of descent from high bourgeois comfort to the stripped-bare nursing home seemed less the image of a great fall, than a journey from 42nd Street to Hoboken with surreal characteristics.

Hold on a minute. There was another case of dementia on Broadway (which closed just recently), one that was also produced by a major off-Broadway institutional theatre, the Roundabout. After its initial off-Broadway success, the play moved to a Broadway theater for an open-ended run. The Humans, by the prolific young Stephen Karam, was touted by the New York Times theatre critic, Charles Isherwood, as the finest new play we will see all season. It concerns three generations of a family assembling over Thanksgiving dinner in a Chinatown basement apartment, such as only New Yorkers would consider a find. This dank, dark, noisy apartment, recently rented by the family’s younger daughter and her boyfriend, becomes the portentous backdrop for a family unraveling.

Mind you, instead of the resentments that traditionally shape American family dramas, this family is awash in love. But the two adult daughters and their beleaguered parents are suffering from the postindustrial condition of precarity (described by Hardt and Negri in Multitude and most recently by Guy Standing in The Precariat): they are losing jobs, or not finding jobs, or working in bars to pay off student debt, or exhausting their savings, or are in poor health, or losing a partner, or…..These are today’s humans.

Cassie Beck, Arian Moayed, Reed Birney, Jayne Houdyshell, Lauren Klein and Sarah Steele in The Humans. Photo credit Joan Marcus

There is one more figure in the play, but she seems to come from a different human register. This is the family’s beloved grandmother, Momo. So far advanced in dementia that she cannot walk or speak two sequential sentences, this little heap of bones, performed by the brilliant Lauren Klein, is tenderly moved from wheelchair to couch and back amidst her periodic outbursts. Her opening speech “You can never come back you can never come back,” etc., is frightening, but her concluding fit seems almost prophetic “Where do we go back to we never go hole you bitch….go back, go back…”

To most critics writing about The Humans, Momo was, you might say, a side of fries, to the ‘burger’ of the younger family members. Momo is interesting, but the play is not about Momo. But… maybe it is. Maybe Momo is the Cassandra of the play. Maybe Karam is saying that dementia is the new death-cry of the human race, the final stage in its extinction. Except, except, Momo is also its shaky redemption, for she is everyone’s beloved relative. She brings out the best in them all. Another meaning of “human.” In fact, the rash of onstage dementia last season may signal that compassion, rather than terror, is gaining the upper hand in the American grappling with this much-dreaded disease. People with dementia are still human.

At the moment it seems that dementia is so last season. I see no sign that Broadway is going to repeat its medical experiment. All four dementia plays closed, with The Humans being the most long lasting (it closed on January 15, 2017). Playwrights might draw the following lesson from its longevity: If you are going to give a character dementia, make sure to give it to a girl (three of the four plays I’ve written about did this), but don’t make her the lead in the show. Let the younger generations thrash on.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Elinor Fuchs.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.