A zoom conversation conducted on 13th May 2021 as part of the Twelfth Between.Pomiędzy Festival.

Tomasz Wiśniewski: The session that we are beginning now is pivotal for all activities conducted by Between.Pomiędzy. We are scholars from Central/Eastern Europe so we are inclined to talk about theatre-makers from this part of the world. Moreover, this is an unofficial launch of 20 Ground-Breaking Directors of Eastern Europe: 30 Years After the Fall of the Iron Curtain, a book that has been edited for Palgrave Macmillan by Kalina Stefanova and Marvin Carlson and that will be published later in May.

Katarzyna Kręglewska: Let me start with introducing our guests. Professor Kalina Stefanova is an author or editor of sixteen books: fourteen books on theatre, and two narratives. She was a Fulbright Visiting Scholar at the New York University and has been a Visiting Scholar at the University of Cape Town (South Africa), Meiji University (Japan), and at the Shanghai Theatre Academy (China), among others. In 2016, she was appointed the Visiting Distinguished Professor of the Arts School of Wuhan University, China, as well as Distinguished Researcher of the Chinese Arts Criticism Foundation of Wuhan University. She served as IATC’s vice-president for 5 years (2001-2006) and as its Director of Symposia (2006-2010). In 2007, she was the dramaturg of the highly acclaimed production of Pentecost by David Edgar, directed by Mladen Kiselov, at the Stratford Festival in Canada. Since 2001, she has regularly served as an evaluation expert for cultural and educational programs of the European Commission. Currently she teaches at the National Academy for Theatre and Film Arts in Sofia.

Professor Carlson is a world-famous theatre, drama and performance studies scholar. He is a Distinguished Professor of Theatre, Comparative Literature, and Middle Eastern Studies and holder of the Sidney E. Cohn Chair at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. He has received an honorary doctorate from the University of Athens, the ATHE Career Achievement Award, the ASTR Distinguished Scholarship Award, as well as many other awards for his scholarly work on theatre. He is a founding editor of the journals Western European Stages and Arab Stages. He is also the author of more than 20 books, translated into 17 languages. Among these are: Theories of the Theatre (1993), Places of Performance (1989), and Performance: A Critical Introduction (1996). His most recent books are 10,000 Nights (Michigan, 2017) and Theatre and Islam (Macmillan, 2019).

I would also like to point out that some other experts on Eastern European theatre are with us: Maria Zărnescu, Michal Zahálka, Octavian Saiu, and others.

Wiśniewski: Can I begin with the question concerning the origins of the volume, and the way in which it was planned?

Marvin Carlson: I have travelled a great deal in Eastern Europe, mostly in Poland. I’ve always found it a wonderful, welcoming part of the world, with incredible theatre. I will pass the speaker role on to Kalina in a moment because this project was conceived and largely directed by her, and she deserves most of the credit for it. I have had the pleasure and honor to work with her, and was enormously impressed. I was already impressed by her work in the Eastern European theatres. The work done in European theatre changes but this work had gone much further and much deeper. It was an enormously rewarding and learning experience for me. I will only say it has been a great pleasure and great learning experience to work with Kalina. I will follow up her remarks with a few remarks of my own, but the main introduction of the project really should be hers, and so I defer to her on that note.

Kalina Stefanova: It has been my privilege to work with Marvin Carlson, it has been a great honor and I have learned so much from his professionalism and his perfectionism. It was in 2016 in Shanghai, when I suggested to Marvin this project and he was very kind to firmly support me from then on until today. So, thank you, Marvin! I would like to really express my gratitude to the Between.Pomiędzy festival, which is a wonderful culture bridge between the theatre and literature. I think our book fits in this profile of yours. Then, I would like to underline my thanks to all 18 contributors who authored the chapters, and all the directors who replied to our questions.

I would like to mention that the festivals throughout Eastern Europe have also been fundamental for this book, because they have provided me with the opportunity to see the wonderful theatre of Eastern Europe, to keep pace with it throughout the years, to be able to come up with the most distinguished names in the world of the theatre in the Eastern part of Europe. So: big thanks to the festivals as well!

As you can see from these acknowledgements, this book is truly a collective work. Also, it is a sample of very productive international cooperation. All the contributors are connected with either the International Association of Theatre Critics or with other theatre circles and institutions.

I would like to underline that although the book offers some kind of an encyclopedic type of information about the 20 directors, i.e. facts, the kind of information which belongs to Wikipedia is not at all its primary focus. Neither, is it only the mechanisms of these directors’ theatre-making process. Of course, this too is there, since it is very important. However, the focus of the book is rather to try and find out some of the answers to the question “why” connected to their work. Namely, why are they creating theatre in the first place? What do they want to say with their theatre? Why do they want to influence and change people, or why is their theatre of a mighty impact no matter if they have intended to change people or not? That kind of area behind the “why” has been the most important to us. It is something that belongs rather to the sphere of wisdom, not so much to the territory of information. Of course, I hope we have created a bridge between Eastern European theatre and English-language readers, especially in English-speaking countries. Eastern European theatre is not well-known there, and our intention has been to make people interested in theatre there be aware as to why these theatre directors are ground-breaking. What is the wisdom their theatre is imbued with? Why is their theatre life-changing, something which I myself have experienced and describe in my foreword?

I would like to quote something that the late critic of Newsweek Jack Kroll said about the transformational power of the arts: “Maybe they’ve never read Ulysses, nevertheless it has affected their life. Maybe they’ve never looked at Picasso, but he has changed their life, whether they know it or not.” The theatre-makers who are included in the book have indeed done this. They have touched people’s soul, no matter whether people have seen their theatre or not.

Recently, I have been reading with my students an article by John Elsom included in the anthology of contemporary British Theatre criticism which I edited at the end of the 1990s. He was a connoisseur of the so-called “Cold War Theatre” as one of his books was called. So, in this article of his – on directors who have been staging Shakespeare – Elsom was comparing British directors with Romanian Silviu Purcărete. He underlined that the reason why Purcărete is so good is in the fact that his skills are nurtured by an academic tradition which is not in vogue in Britain and which is kind of disappearing in Eastern Europe. And these skills of Purcărete, continued Elsom, are rooted in what were called in the past human sciences, whose main aim is attaining wisdom rather than information. This fits exactly into our own main goal with this book.

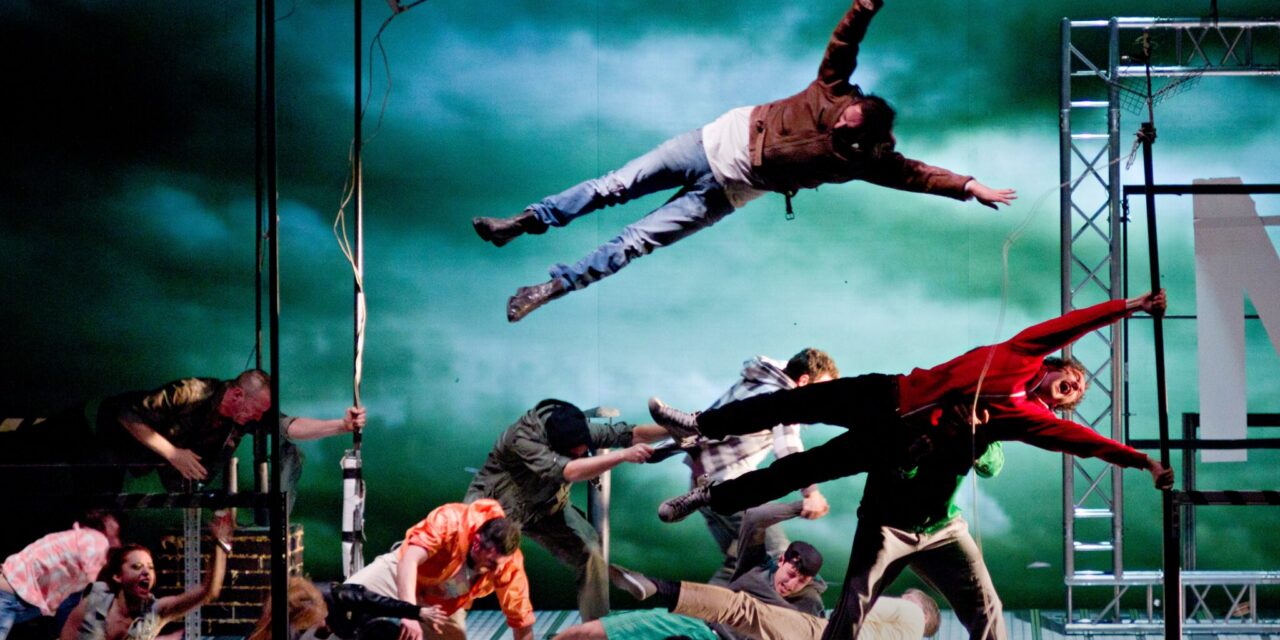

Faust, directed by Silviu Purcărete, Radu Stanca National Theatre, 2007. Photo by Mihaela Marin.

I should stress that the aim of our book is not to introduce the whole theatre of Eastern Europe. That would require another volume, so that country by country the theatrical landscape could be outlined. That would also require a more inclusive approach. This is certainly not the aim here. There are countries which are not represented at all and, at the same time, there are many directors from Poland, many more than from any other country. We wanted to concentrate on the ground-breaking directors of these last three decades. Of course, there are many more than twenty, and it was extremely difficult to bring them down to twenty. It was a result of lots of consultations with theatre colleagues, both theatre critics and theatre makers in Eastern Europe, to come down to these names. But I would like to again underline: there are many more directors whose theatre is life-changing.

All that said, I hope, together with getting to know the theatre of the twenty directors included in the book, our readers will be able to get a general notion of the Eastern European theatre throughout the last 30 years. It is, indeed, on a very high level, and it’s not by chance that the European Prize for (New) Theatrical Realities – the second big European theatre award – has gone very often to Eastern European directors. And the major award, the Europe Theatre Prize, too, has gone to a director from Eastern Europe – Krystian Lupa, as a special award has gone to Purcărete. In brief, we have tried to open a window. Hopefully, there will be another volume one day that will add more names. This is my short introduction and I would like to give the floor back to Professor Carlson and to other contributors.

Wiśniewski: However, before that, I would like to add one or two sentences to what Kalina has said and what was present in this introduction. In a sense, for scholars living in this part of the world, the question of identity is always vital. The question of how the experience of the last 30 years has been lived through by other people, other nations, other scholars, and other theaters all around us. Monika Sznajderman, who is an important publisher in Poland, and a prominent writer – and who focuses on Central-Eastern Europe – expressed her disappointment that after the fall of the Iron Curtain, we ceased to ask questions such as: “How’s life in Bulgaria?”, How’s life in Romania?”, “What about life in the Czech Republic?” We were so fascinated with the Western world, with America, with Western Europe, that we ceased to be curious about our neighbors. Professor Carlson, please forgive me this interruption but this recollection strongly resonated with what Kalina has just said. Among other things, this book has encouraged us to get to know one another.

Carlson: Tomasz, thank you for that intervention. Very helpful and useful. I think I have to begin by saying that, speaking as an American and as somebody with a very profound interest in theatre and international theatre, it has struck me a number of times as strange that the last twenty or thirty years in the United States there has been so little awareness of what was going on in Eastern European theatre. We always have had a closer relationship and knowledge of France, Germany, England than we had with, say, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria and so on, and there are many historical reasons for that, but it is also true that in the twenties, thirties and forties we were aware of Hilar and people like that doing interesting and important work in Eastern Europe. And then, of course, during the Cold War, anybody in the United States that was interested in theatre, of course, knew Jerzy Grotowski, and Tadeusz Kantor. These were household names that all my students would know. Ironically, surprisingly, after that we had Eimuntas Nekrošius and Silviu Purcărete, but they had both toured in the United States, and people who have recently come on the scene sensed those two are totally unknown in the United States – which is not only ironic but surprising, in that our knowledge now, our awareness of what’s going on in the very appealing, very attractive, very enticing Eastern European theatre, is less than during the Cold War.

You would think “Oh, once the Cold War has ended, the Wall is down, we will be much more aware of what they’re doing”. That has not been the case, which is very sad, and which once again focuses on why this particular book is so important! That there is not much of anything – of any systematic nature, in English – about this theatre. And so it has been a great pleasure to be just working on the project, because it is simply an interesting one, but even more, it is been a kind of mission for me, because it is so important, and so necessary. I have had the pleasure of traveling around Eastern Europe and going to some of the festivals there, and certainly we have transplanted a little bit of Eastern European when Andrei Șerban was with us in the United States, with a great deal of influence as well. What you said, Tomasz, about us not being aware of it, of these influences – we tend to reflect it and that’s certainly true. That should also whet our appetite for knowing what is being reflected, what other cultural activities we should be aware of. For all of those reasons, particularly as an American, even more so than if I were French, or German, or English, I feel the enormous need for and contribution of this book.

To read PART 2 and PART 3 of the interview, click the links.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Tomasz Wiśniewski and Katarzyna Kręglewska.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.